|

On a spectacularly green, blue, and breezy day this past June,

I headed to Small World Coffee for a mid-morning cortado and some al fresco reading on the busy shores of Princeton’s Nassau Street. Over my last several cafe visits I had been happily re-reading The Accidental Connoisseur,

Lawrence Osborne’s superb wine odyssey memoir, but this day, perhaps due to the heightened potency of the outdoors, I reached for something different . . . and stronger. I

grabbed my copy of Hymns and Fragments by Friedrich Hölderlin, translated by Richard Sieburth.

For quite some time now, I almost exclusively read nonfiction.

I can count on one hand the novels I’ve read in the last five years.

However well-crafted, fiction reaches me less and less; I just prefer reality. And if fiction has become a rare choice, poetry is rarer still–strange, you may think, since

I’m a poet, but I have my reasons.

So it was unusual that I’d bring a book of poems along, but I played a hunch. Still, I couldn’t have imagined how incredibly receptive

I’d be to re-reading those familiar lines. Within minutes, Hölderlin’s lyrical genius mastered me, bearing me along in a swoon of true poetic transport.

Not for nothing: on any given day, his wildly beautiful ode,

“The Rhine,” is my favorite poem.

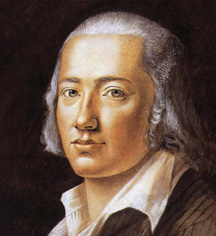

You may not know Friedrich Hölderlin. In Germany he’s legendary and justly beloved, considered by many the greatest

poet in the language. He lived from 1770 to 1843, a central figure of German Romanticism. As a Romantic poet, he shared many similarities of outlook and endeavor with his English

contemporary William Blake (1757-1827). Like Blake, Hölderlin fashioned his own highly idiosyncratic cosmology, a mystical

conception of the world embracing God, gods, and demigods. And like Blake, he viewed Nature as holy, deserving of awe in the true sense: a blend of rapt regard and fear.

Rivers abound in Hölderlin’s poems–the Danube, the Ister (an ancient Greek name for the Danube), the Rhine, the

Neckar–because for him they are not mere bodies of moving water but demigods incarnate.

He makes pronouncements, his voice truly and fittingly oracular, though he never comes off as didactic. His power and

conviction transcend any questioning; he says it and you accept it, his purchase sure, unassailable. Here’s Hölderlin concluding “The Migration”:

But the handmaids of heaven

Are miraculous,

As is everything born of the gods.

Try taking it by surprise and it turns

To a dream; try matching it by force,

And punishment is the reward;

Often, when you’ve barely given it

A thought, it just happens.

And here, midway through “The Rhine,” he shares deep insights into the nature of deities:

But their own immortality

Suffices the gods. If there be

One thing they need

It is heroes and men

And mortals in general. Since

The gods feel nothing

Of themselves, if to speak so

Be permitted, they need

Someone else to share and feel

In their name; yet ordain

That he shall break his own

Home, curse those he loves

Like enemies, and bury father and child

Under rubble, should he seek

To become their equal, fanatic,

Refusing to observe distinctions.

His syntactical transitions are one of the most curious and

compelling aspects of his poetry. Using words like “still,” “but,”

“yet,” and “even,” he pivots, often to startling effect, juxtaposing one insight with another, leading you down marvelous twists

and turns. He learned this technique, at least in part, from Pindar, the ancient Greek poet of Thebes renowned for his odes

commemorating victories at the Olympic and Pythian games. Hölderlin was no mean Hellenic scholar and is still considered Pindar’s finest translator into German.

Here’s how Pindar comes out of the gate in his first Olympian Ode, the translation by Richmond Lattimore:

Best of all things is water; but gold, like a gleaming fire

by night, outshines all pride of wealth beside.

But, my heart, would you chant the glory of games,

look never beyond the sun

by day for any star shining brighter through the deserted air,

nor any contest than Olympia greater to sing.

And here’s Hölderlin in the penultimate stanza of his ode to the mighty river Rhine (and a passage I so dearly love that I’ve had it

memorized for decades.)

The eternal gods are full of life

At all times; but a man

Can also keep the best in mind

Even unto death,

Thus experiencing the highest.

Yet each to his measure.

For misfortune is heavy

To bear, and fortune weighs yet more.

But a wise man managed to stay lucid

Throughout the banquet,

From noon to midnight,

Until the break of dawn.

You know, Hölderlin considered the poet’s role as that of an intermediary between gods and mortals, but–stay with me

here–if you’re familiar with The Godfather Part II I want you to imagine Hyman Roth (Lee Strasberg) saying the lines of that

stanza to Michael Corleone and the other guests as they sit out on the hotel terrace in Havana enjoying Roth’s birthday cake.

Give due credit to Richard Sieburth for preserving the intensely romantic musicality of the lines through deft use of rhyme, slant

rhyme, assonance, and alliteration (i.e. poetry’s fundamental tools; i.e. the same tools eschewed for years by our many prolific

poetasters.) And while he translates a work over 200 years old (Hölderlin began writing “The Rhine” in 1801), Sieburth avoids

rendering the poem archaic with inverted syntax or other anachronisms; the lines read fresh and direct.

The Rhine is a demigod unto itself, but Hölderlin will compare it to Hercules, its tributaries to thirsty snakes. And while he

dedicates the poem to his friend, Isaak von Sinclair (whom he addresses directly in the last stanza), Hölderlin also turns to

Enlightenment philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the great champion of human nature who, appropriately enough, began his famous treatise, The Social Contract, with the declaration:

“Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.” In Hölderlin’s visionary portrayal, the mighty river will find itself in the same predicament.

So here it is in full, my candidate for greatest poem of all time. Want to take a fantastic trip down a river without leaving your

seat? Want to glean wisdom without those attendant crow’s feet and white hairs? Turn off your cell phone and disable any of

those other electronic distractions the hucksters call “progress.” Now summon your kids, your favorite co-workers, your spouse,

or your mail carrier and tell them you have something you’d like to read to them….

The Rhine

To Isaak von Sinclair

I was sitting in the dark ivy, at the gate

Of the forest, just as the spring was visited

With the gold of noon pouring

Down the steps of the Alps

Which I call the fortress of the gods

In the ancient sense, architected

By the heavens, and from which

Many decrees are still mysteriously

Handed down to men; there,

Against all expectation, I grew aware

Of a fate, even as my soul,

Lost in its own conversation

In the warm shade,

Had already wandered off to Italy

And beyond, to the shores of Morea.

But now, within the mountains,

Deep beneath the silver peaks

And joyous green,

Where shuddering woods

And boulders, head over head,

Look down on him, days

On end, there, in coldest

Abyss, I heard the young man

Moan for deliverance,

Hurling blame at Mother Earth

And his father, the Thunderer,

And his parents felt compassion

For his raving, but mortals fled

The place, terrified by the demigod’s

Rage as he wrenched at his chains

In the dark.

It was the voice of the noblest of rivers,

The freeborn Rhine,

Whose hopes lay elsewhere when he left

His brothers, Ticino and Rhône, behind,

Bent on adventure, impatiently driven

Towards Asia by his royal soul.

But desire is foolish

In the face of fate.

Yet the blindest

Are sons of gods. For man knows

His house, animals realize

Where to build, but these others

Fail in their inexperience,

They know not where to go.

A riddle, the pure of source. Which

Even song may scarce disclose. For

As you began, so shall you remain,

And though need

And nurture leave their mark,

It all depends on birth,

On the ray of light

The newborn meets.

But where is the man

Who can remain free

His whole life long, alone

Doing his heart’s desire,

Like the Rhine, so fortunate

To have been born from

Propitious heights and sacred womb?

His Word is hence a shout of joy.

Unlike other children, he does not

Whimper in swaddling clothes;

For when riverbanks start

Sidling up to him, crooked,

Coiled in thirst,

Eager to draw him, unawares,

Into the shelter

Of their teeth, he laughs

And tears these snakes apart,

Plunging onward with the spoils,

And if no higher power tamed his rush,

He would grow and split the earth

Like lightning, as forests hurtled in his wake,

Enchanted, and mountains crashed to the ground.

Yet a god would spare his sons

A life this rash and smiles

When rivers rage at him as this one does

From depths, intemperate,

Though hemmed by holy Alps.

In such forges the unalloyed

Is hammered into shape, and

It is a thing of beauty when he leaves

The mountains, content to flow

Quietly through German lands, his longings

Stilled in fruitful commerce, and

Works the soil, feeding the children

In towns he has founded,

Father Rhine.

But he shall never, never forget.

Human law and habitation would sooner

Perish and the light of man

Be twisted beyond recognition, than

He forget his origin,

The pure voice of his youth.

Who was it who first

Wrecked the bonds of love

And transformed them into chains?

Which led rebels to make

A mock of their rights

And the heavenly fire and,

Disdaining mortal ways,

Elect presumption,

Striving to become the equals of gods.

But their own immortality

Suffices the gods. If there be

One thing they need

It is heroes and men

And mortals in general. Since

The gods feel nothing

Of themselves, if to speak so

Be permitted, they need

Someone else to share and feel

In their name; yet ordain

That he shall break his own

Home, curse those he loves

Like enemies, and bury father and child

Under rubble, should he seek

To become their equal, fanatic,

Refusing to observe distinctions.

Hence happy is he who has found

A fate to his proportion

Where the memory of trials

And travels whispers sweetly

Against stable shores,

So that his roving eye

Reaches as far as the limits

Of his residence, traced

By God at his birth.

He rests, content with his station,

Now that everything he desired

Of heaven surrounds him

Of its own accord, smiling on him,

Once so headstrong, now at rest.

It’s demigods I think of now,

And there must be a way in which

I know them, so often has their life

Stirred my breast with longings.

But a man like you, Rousseau,

Whose soul had the strength to endure

And grow invincible,

Whose sense was sure,

So gifted with powers of hearing

And speaking that, like the winegod,

He overflows and, divine and lawless

In his folly, makes the language of the purest

Accessible to the good, but justly blinds

Those sacrilegious slaves who could not care,

What name should I give this stranger?

The sons of the earth, like their mother,

Love everything, and accept it all

Without effort, lucky ones.

Which is why surprise and fright

Strike mortal man

When he considers the heaven

He has heaped upon his shoulders

With loving arms, and realizes

The burden of joy;

So that it often seems best

To him to remain forgotten

In the shade of the woods,

Away from the burn of light,

Amid the fresh foliage of Lake Bienne,

Caring little how poorly he sings

Schooled, like any beginner, by nightingales.

And it is glorious to arise

From holy sleep, waking

From the forest cool, and walk

Into the milder evening light,

When He who built the mountains,

And traced the course of streams,

He whose smiling breezes

Filled the busy, luffing life

Of man like sails,

Now rests as well,

And finding more good

Than evil, Day, the sculptor,

Now bends towards

His pupil, the present Earth.

Men and gods then celebrate their marriage,

Every living thing rejoices,

And for a while

Fate achieves a balance,

And fugitives seek asylum,

The brave seek sleep,

But lovers remain

As before, at home

Wherever flowers exult

In harmless fire, and the spirit

Rustles around dim trees, while

The unreconciled are now transformed,

Rushing to take each other’s hands

Before the benevolent light

Descends into night.

For some, however, all this

Quickly passes, others

Have a longer hold.

The eternal gods are full of life

At all times; but a man

Can also keep the best in mind

Even unto death,

Thus experiencing the highest.

Yet each to his measure.

For misfortune is heavy

To bear, and fortune weighs yet more.

But a wise man managed to stay lucid

Throughout the banquet,

From noon to midnight,

Until the break of dawn.

Sinclair, my friend, should God appear

To you on a burning path under pines

Or in the dark of oaks, sheathed

In steel, or among clouds, you would

Recognize him, knowing, in your youth,

The power of Good, and the Lord’s

Smile never escapes you

By day, when life

Appears fevered and chained,

Or by night, when everything blends

Into confusion, and primeval

Chaos reigns once more.

|