|

I have always been drawn to the poet John Keats, but last year, my search for a more personal understanding of the

man behind the genius bore some very special fruit, when he became the subject of an opera libretto I wrote for the Emmy-award-winning composer Daniel Steven Crafts. Crafts has

just finished the score to Adonais, and both of us are excited and eager to give the piece a first performance.

Writing the libretto, which draws extensively on Keats’ poems and letters, brought me once again face to face with an artist, whose

brief life and his natural reserve partially account for his elusiveness. It also took me back to my graduate study years when Keats and Shelley became my areas of

concentration, but more vividly it allowed me to revisit, in my journalistic articles and in my memories, the places associated with the poet, most particularly the house

at Hampstead Heath where he spent his last days in England and the room at the foot of the Spanish Steps in Rome where his life came to a close at the age of twenty-six.

John Keats aspired to be a poet and despite difficult financial circumstances and poor health, gave up his studies as a surgeon

to pursue his Muse. Recognized early on by influential men of letters like Leigh Hunt, who championed his initial works, and

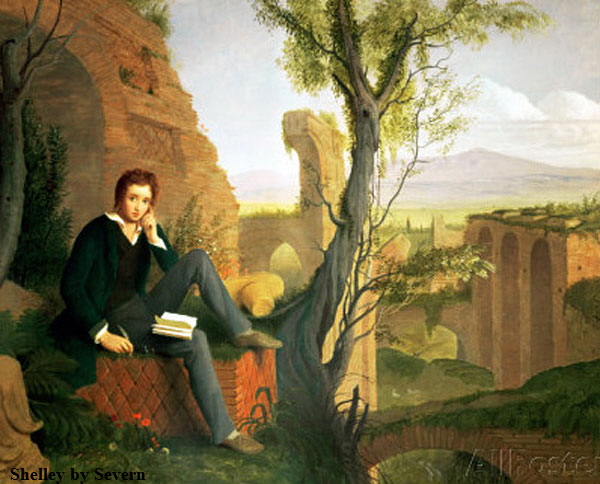

Percy Bysshe Shelley, who generously praised Keats’ genius and offered him personal assistance in his last illness, Keats struggled

for literary recognition among the London establishment from the publication of his first verse in 1816 until he laid down his pen in

1820.When it was published in 1818 , his first long major poem, Endymion was savaged by the critics (giving rise to the

posthumous myth that it was they who had killed the tubercular poet). His brother George emigrated to America while his other

brother Tom succumbed to tuberculosis, as had their mother before, leaving Keats weak and ill from nursing them. Still in 1819

after leaving London and taking up residence in Hampstead, Keats experienced his annus mirabilis. His great odes date from this time, as do his narrative and epic poems, The Eve of St. Agnes

, La Belle Dame Sans Merci, Lamia, and Hyperion. It was almost as if he knew time were running out.

He was displaying symptoms of what he called “the Keats family

illness,” but there were other motivations to stir his imagination. Not the least of these was Hampstead itself – an idyllic village on

the outskirts of London, where he could cultivate his sensitivity to the natural world. But then, too, there was another inspiration:

Fanny Brawne. The Brawnes occupied the other half of what was then called Wentworth House, while Keats and his friend Charles

Brown shared the adjoining part. Fanny Brawne, the eldest daughter, soon captured his fancy, and though the poet was in no

position to begin a serious romance and though Fanny’s family discouraged her, the pair fell in love, and despite advice to the contrary became quietly engaged in 1819.

In 1820, however, Keats suffered a severe hemorrhage, and literally dragged himself back from London to Hampstead,

collapsing on the Brawne’s lawn. Mrs. Brawne and her daughter, together with Brown nursed him until the fall when, at the advice

of his doctors and with the financial help of his friends, he sailed for Italy. Told that another English winter would surely kill him,

Keats had little choice, though parting from Fanny was agonizingly painful. She had begged to marry him and accompany

him, but neither her mother nor Keats, himself, would allow her to make that sacrifice. Instead, the young painter Joseph Severn

became the companion of Keats’ last days, sailing with him to Naples and then traveling to Rome, where they installed

themselves in a small apartment at the foot of the Spanish Steps. Keats wrote no more, declined steadily, and died on February 23,

1821. Severn and the English community arranged for his burial at the Protestant Cemetery in Rome beneath the Pyramid of Caius

Cestius. A little more than a year later, Shelley, who had written Keats’ eulogy in the beautiful Adonais, would also be interred

there, having been drowned off Leghorn, a copy of Keats’ Hyperion in his pocket.

Both houses associated with Keats’ last years have been lovingly preserved, and the poet’s presence seems palpable in each, and

despite the changes wrote by time, a visit seems to take the pilgrim back almost two centuries. Nestled on the still idyllic

heath in a hamlet about twenty miles north of London is the elegant white stucco cottage surrounded by a low wall and

climbing rose bushes. Under a spreading yew tree stands a garden seat on which legend has it, Keats sat to write his famous odes,

listening to the nightingale, or drinking in the beauty of autumn. To the right, connected by a breezeway is a twin cottage, once the

Brawne residence and now the Hampstead Public Library and Keats Museum.

The place echoes with a poetic melancholy. It was here and in their walks on the neighboring heath that he “tutored” Fanny in

the language of poetry, and here that an unconsummated passion for her filled Keats’ last days in England with ardor and tension.

And finally, it was here that Keats wrote “Ode to a Nightingale,”

“On a Grecian Urn,” “On Indolence,” “On Melancholy,” and “To Autumn.”

Reflecting Keats’ state of mind, the odes are masterpieces of passion and restraint, pulsating with a richness of imagery,

compact with thought and power. Not only do they speak to the mastery of the poet’s craft and vision, but they present powerful

responses to life and death in both the personal and universal sense. Ever awake to the concrete sensuousness of the world

around him, Keats captured the spirit of Wentworth Place and Hampstead Heath, as well as the landscape of his soul, in all the

odes, most especially in “On Melancholy” and his final major poem, “To Autumn.”

The poet begins the first stanza of his meditation on melancholy by ordering the reader not to submit to the seductive pull of Lethe

. The death wish – “to cease upon the midnight without pain” as he phrases it in the nightingale ode – is here rejected in favor of

the act of grappling with death for in that very struggle lies life itself. The desperate race against time is also felt in the

concluding lines of the stanza where Keats cautions, For shade to shade will come too drowsily/ And drown the wakeful anguish of the soul. In the second stanza Keats speaks of melancholy and

anger, contraries which enrich life, and he surely refers to the tensions in his relationship with Fanny in his advice to lovers that if thy mistress some rich anger shows,/ Emprison her soft hand

and let her rave,/ And feed deep, deep upon her peerless eyes. Throughout the ode melancholy is personified as a woman; she is

associated with Beauty, with his mistress, with love, and inextricably also with death.

A whole series of oxymorrah dot the stanza – Joy whose hand is ever at his lips/Bidding adieu, for example – conveying Keats

frustration at his circumstances and his hopeless love for Fanny. Yet, the poet closes the ode with an heroically courageous and

vibrantly sensuous image. Rejecting self-pity, doubt, or despair, the poet concludes: Though seen of none save him whose

strenuous tongue/Can burst Joy’s grape against his palate fine;/ His soul shall taste the sadness of her might,/And be among her cloudly trophies hung. He who can – with physical passion –

taste, exploit, ravish life and joy to the fullest, will know sorrow, too, in the same measure. Melancholy will triumph over him, but

he will have experienced the depths of passion that give meaning to his life.

The elegiac “To Autumn,” written in September of 1819, evokes much of the same mixture of melancholy and valiant optimism.

This ode is a far quieter piece, more accepting than “On Melancholy.” It seems to reflect the poet’s ebbing physical

strength. He sees himself as powerless before his destiny; there is a tone of nostalgia that couches everything in the past. The race

against time, fought so desperately in the earlier ode, is here a lost battle. Yet in the flickering twilight the frail poet still clings to life

with an inexhaustible, affirmative beauty.

Image after fecund image fills the poem with a glowing ripeness: seasons of mists and mellow fruitfulness, maturing sun, to load

and bless with fruit the vines.

Keats seeks to die, if he must, of surfeit – to fill himself with the

joy of living so as to render the pain secondary. There are sweet, soft images of Autumn, seen as the beloved, caressed by the wind,

perfumed by the drowse of poppies, as well those of Autumn as the gleaner, squeezing out the last oozings hours by hours. Keats interjects a plaintive note when he asks, Where are the songs of

Spring? Ay, where are they?, but he dismisses this thought with Think not of them, thou hast thy music, too. The poem segues

into a glut of somber, muted images – barred clouds bloom the soft-dying day and touch the stubble plains with rosy hue or the wailful choir of small gnats mourn. But amid this feeling of

drowsiness and creeping death come several final stirring lines: And full grown lambs bleat loud from hilly bourn;/ Hedge

crickets sing; and now with treble soft/The red breast whistles form a garden croft/ And gathering swallows twitter in the skies. This chorus of song blends into a harmonious medley as the

poet’s vision travels upward with the swallows toward the heavens.

The poem ends, as it were in midair. There is no resolution, nor any real wish for transcendence. Rather Keats sees death less as a

terminating force and more as a stage in a natural, continuing cycle. The poet, so involved with life’s concrete glories, must live

the autumn of his days to the fullest, sing its songs, share its harvest, and if, in so doing, he passes into the hands of the Reaper

, then so be it. Dying becomes simply a courageous act of living.

Alas, Keats’ courage would be sorely tested in the coming months. The single bright spot of that year was the well-received

publication of Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St Agnes and Other Poems in July. In February of 1820 he had suffered his first

debilitating hemorrhages and in September of that year he embarked with Severn for Italy, arriving in Rome on November 14,

1820. Despite the Brawnes’ ardent wish that he return to marry Fanny, Keats instinctively knew he would never see his fianc├ęe or

England again. His letter to Charles Brown on November 30 of that year contained the last known words he ever wrote.

Keats and Severn took rooms at the foot of the Spanish Steps in

the heart of the Eternal City’s “English Quarter.” From the dark paneled interior the poet had a view of the crowded steps, dominated by the majestic Trinit├á dei Monti above as well as the

Bernini fountain which presides over the piazza. It was the lulling sound of the water that caused the poet to dictate to Severn his

own simple epitaph: “Here lies one whose name was writ in water. “In three short months Keats declined rapidly, misdiagnosed by

his English physician. In his last days he was confined to the tiny bedroom with its ceiling of carved, gold-leafed squares embossed

with flowers, and in his delirium he remarked to Severn that “the flowers [are] growing over me.” He refused to open any of Fanny

Brawne’s letters to him, fearing the emotional impact he knew they would make, and instead, he asked Severn to place them on

his heart in his coffin – a request Severn honored, thereby depriving posterity of these documents. Tormented by the

ravages of the disease, he desperately asked “when this posthumous existence of mine will end?” The end did come late

on February 23, when he called for Severn to lift him up and not to be afraid.

It fell to Severn to handle all the final arrangements. Vatican law proscribed burning all the furniture and draperies to “prevent the

spread of infection.” The painter and the English community secured a burial for the poet in the Protestant Cemetery where

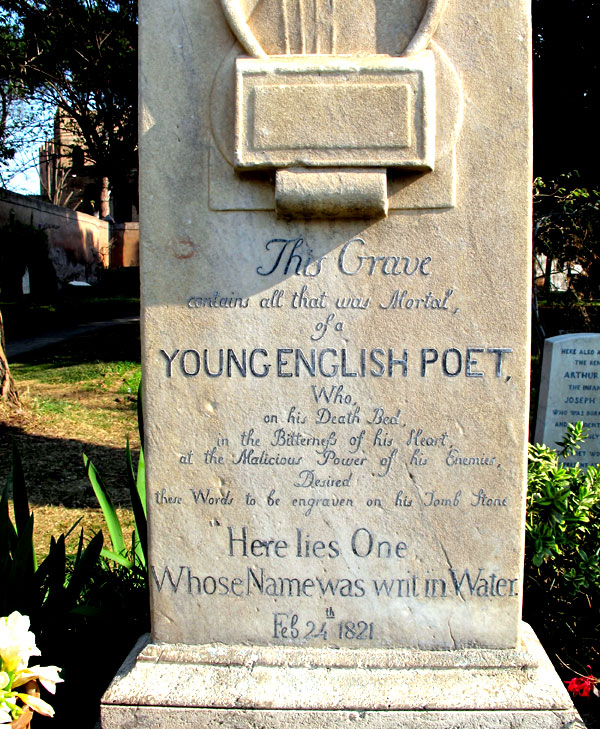

not long after he and Charles Brown had erected a stone on which is engraved a broken lyre and an inscription, which while it does

not name Keats, identifies him as a young English poet who / on his Death Bed, in the Bitterness of his Heart / at the Malicious

Power of his Enemies / Desired / these Words to be / engraven on his Tomb Stone: / Here lies One / Whose Name was writ in Water.

If Keats' poetic presence seems to penetrate the walls and meadows of Hampstead Heath, his silence is what rings out with

poignant clarity in the room in Rome and beneath the graveyard’s pyramid. Instead of Keats’ voice, as one visits Rome, one hears

the immortal words of Shelley’s great elegy, Adonais, which ironically not only mourned a fellow poet, but seemed to foresee

Shelley’s own imminent death, where in the closing stanzas Shelley offers these consolations

He lives, he wakes—'tis Death is dead, not he;/Mourn not for

Adonais…..He is made one with Nature… He is a portion of the loveliness/Which once he made more lovely…

before he imagines himself embarking on the journey in which Keats has preceded him:

I am borne darkly, fearfully, afar;

Whilst, burning through the inmost veil of Heaven,

The soul of Adonais, like a star,

Beacons from the abode where the Eternal are.

It is with these words that I closed my libretto for Daniel Steven Crafts, who set them for chorus, bringing full circle the opera from

its poignant melodic choral opening in which the music of the fountain and Keats’ epitaph antiphonally replies to Shelley’s O weep for Adonais, he is dead. To hear Crafts’ music is to transport

me back to Hampstead and then to my last visit to Rome more than a decade ago.

While paying our respects to the Keats house at the Spanish steps, I remarked to my husband Greg that the poet’s story was so

operatic. “You should write it,” he challenged me. I shrugged and laughed, “I doubt anyone will ask me to.” Fast forward fifteen

years. When Crafts and I agreed on a subject for our collaboration, I didn’t remember the comment. It was only after I had finished

the manuscript, and Danny and I were exchanging letters that Greg’s words came back to me, and I realized that in a way, I had just completed a journey.

|