|

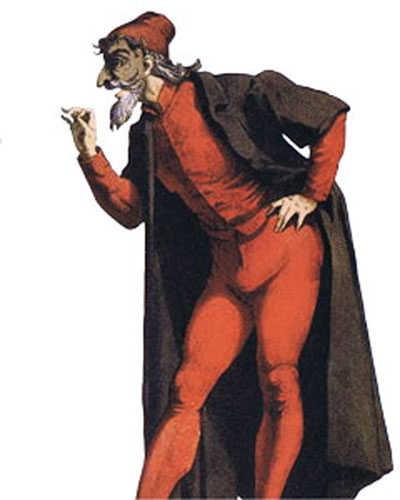

The Commedia dell’Arte was the theatre of the mask. The entire essence of the tradition, born in Renaissance Italy, was founded on the concept of stylized illusion. It is a folk art which draws amply from life, welding together direct observation with profound humanism. The device largely responsible for this artistic union is the mask that allowed the artist to present reality as he saw it behind the guise of conventionalized dramatic illusion.

One of the most celebrated practitioners of the Commedia,

Carlo Gozzi (1720-1806)

literally used masks in

his work and fashioned his

characters in the

conventional mode of

traditional stereotypical

roles – Pantalone,

Brighella, Arlecchino, the

Innamorati.

But his contemporary and

rival, Carlo Goldoni

(1707 -1793), while

he was also deeply

influenced by the Commedia tradition, took the bold step of abolishing the physical mask in his plays. With Goldoni a new form of Italian comedy is born. His art is subjective rather than symbolic; it turns away from exterior concerns toward the complexity of human existence.

Goldoni believed the mask hindered the actors from delving into the

psychology of a character; it created a barrier between actor and

audience. Unlike the earliest Commedia plays, Goldoni abandoned all

improvisation, scripted the stage business and text, and relied mostly

on prose rather than the affected and heightened poetics of Gozzi.

Moreover, he sought to add to the physical comedy of the Commedia

tradition, a layer of comedy of manners; Goldoni’s work explores

human nature in all its foibles and holds a glass to social behavior.

The direction that Goldoni’s work took was bolstered by the

transformation writers like Moliere (1622-1673) had wrought on the

imported Commedia dell’Arte. From Moliere’s work Goldoni gleaned

wit, tenderness, compassion, and he imbued his plays with an intimacy

and connection between actor and audience that have made them

timeless.

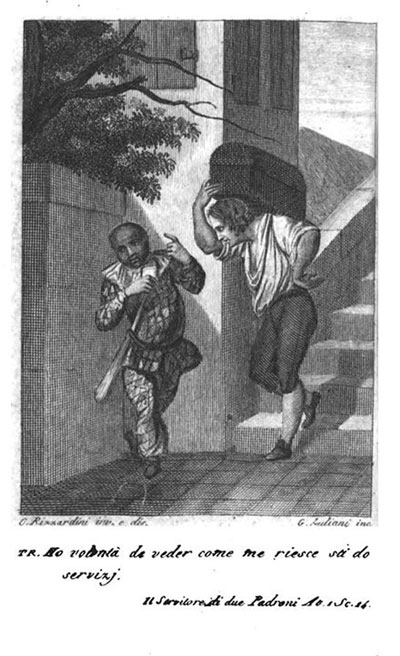

Goldoni’s most famous work remains The Servant of Two Masters,

though this is one of his earliest and actually most conventional plays.

It makes use of all the traditional Commedia characters as well as the

devices of mistaken identity, thwarted romance, and a wily servant. It

is classic, quintessential farce relying on the high-energy performance

of its protagonist, Truffaldino. But the attention and insight Goldoni

lavished on Truffaldino elevates this character, even in this early play,

to a multi-dimensional role. Truffaldino is interesting to modern

audiences not only because he creates the bungling intricacies of the

plot, but also because he is an individual who intrigues us because we

share his actions AND his feelings. Truffaldino is a delightful rogue –

amorous, self-interested, grasping, scheming, hungry, and fiercely

clever. He invites audience identification and empathy; his boldness,

his unabashed plebian spirit, and good-humored errors endear him to

the audience. Truffaldino stands head and shoulders above the rest of

the cast in that he is the first of Goldoni’s long line of personages who

emerges from behind the mask – literally and figuratively.

Though almost four hundred years old, The Servant of Two Masters

remains an icon of classical theatre, receiving countless productions

through the centuries and being adapted into modern retellings. One

such lively and captivating version is Richard Bean’s 2012 play, One

Man Two Guvnors, which sets the tale in Brighton, England, in the

1960s. A recent production staged by Portland’s Good Theater is a side

-splittingly funny, perfectly timed farce that honors the work’s ancient

roots in Italy’s Commedia dell’Arte. Bean reveals the enduring

universality of Goldoni’s characters and the predicable, but perfect,

recipe for comedy. The Good Theater’s production, though small in

scale, is large in impact, delivering an evening of hearty laughter and

impeccable comedic technique by the eleven-member cast, led by the

irrepressible Dustin Tucker in a role which he was born to play.

Playwright Bean’s script follows Goldoni’s scenario about a hapless

servant who hires himself out to two masters in an effort to assuage his

hunger and make ends meet. However, he must also make certain

neither employer learns of the other, and he spends the better part of

the play’s two plus hours devising a harrowing a list of schemes to

make his plan work. In the process, he becomes involved in his

“guvnors’” complicated lives, is forced to play two characters, himself,

and has his wits and energy sorely tested in a series of madcap, near

-miss scenes. In classic Commedia fashion, all is happily resolved and

revealed in the closing moments of the play, as the entire cast launches

into the song/dance celebration, Gary Olding/Richard Bean’s

“Tomorrow Looks Good from Here.”

Both the Commedia original characters and Bean’s are stereotypes

with prescribed roles in the comedy, and Bean’s superimposing onto

the originals a cast of mobster families in 1960s Brighton, while staying

true to the essence of the genre, works with sassy contemporary

charm.

Sally Wood directs with a sure hand for pacing and a flair for the

physical comedy this play upon which relies so heavily. She keeps the

kinetic flow going at a madcap pace and encourages, especially for the

protagonist, Francis Henshall, the kind of improvisation inherent in

the genre.

Despite the confines of the small stage at the Good Theater, set

designers Steve Underwood and Tracy Washburn (Props Meg

Anderson) manage to create an attractive, minimalistic set that serves

as multiple locales with some simple changes. Colorful, slightly two

-dimensional, the décor has the feeling of a children’s storybook,

adding to the improbable magic of the piece. Ian Odlin’s lighting

reinforces the effect, while Michelle Handley’s costumes capture the

period. The uncredited sound design with a series of tracks from the

1960s is delightfully atmospheric. Technical Director Craig Robinson

Stage Manager Michael Lynch keep the tricky timing of the show

running perfectly.

The eleven-member cast is comprised of quite a few actors making

their Good Theater debut, as well as Good veterans. As an ensemble,

they do a credible job of the working-class British accents and

demonstrate an affinity for the style of the piece. Paul Haley is

appropriately pompous and bombastic as the attorney Harry Dangle,

while Mark Rubin is all gangster toughness as Charlie “the Duck”

Clench. Morgan Amelia Fanning makes Pauline Clench a delightfully

dim ingenue with a vacuous gaze, piping voice, and flouncing blonde

wig. As her suitor Alan Dangle, Pierce Ducker creates the perfect

parody of a self-declared poet and actor, turning his scenes into comic

melodrama. As the second pair of star-crossed lovers, Heather Irish

camps prettily Crabbe impersonating her supposedly dead brother,

while Nathaniel Stephenson plays her lover, Stanley Stubbins as a

clueless, spoiled, self-satisfied gentleman. As other servants and

retainers, Ashanti Williams (Lloyd Boateng), Daniel Cuff (Gareth), and

Ethan Rhoad (Alfie) contribute amusingly to the general mayhem. On

the evening I attended due to the illness of Molly Bryant Roberts, the

role of Dolly, Henshall eventual love interest, was taken over by

Director Sally Wood, who heroically kept the evening going while

discreetly referring to a small script.

But as the title of the play suggests, there is one man – and one actor –

at the heart of the action. Dustin Tucker, well known for his talent at

playing multiple characters in a single show and creating brilliant one

-man shows, is nothing short of dazzling as Francis Henshall (and his

various identities like Paddy). At once impish, winsome, endearing

and then scheming, manipulative, opportunistic, Tucker is the perfect

Harlequin figure at the center of this Commedia script. A bundle of

seemingly inexhaustible energy, he is a master of the physical comedy

the play demands, at the same time, that he is skilled at the verbal

intricacies and tongue twisters that punctuate the dialogue – not to

mention the note-perfect use of accents. And, most of all, he is an

accomplished improviser – riffing deliciously on Goldoni’s script and

stage business – devising physical and verbal business that convulses

the audience in laughter. The eating scene in which Henshall attempts

to serve both masters an elaborate dinner, while stealing some for

himself is pure revolving door farce capped by an hilarious exchange

with an audience member.

In the final scene when convention requires for the farce to unravel,

the pairs of characters to be matched, and a happy ending to ensue, One Man Two Guvnors ends, as would the 18th century Goldoni play,

with a song and dance by the ensemble. This time the number is an

original composition (Bean/Olding), “Tomorrow Looks Good From

Here,” and the sheer exuberance of the cast, as they each get a chance

at the mic and dance with glee, signals the joy created by the evening.

This is comedy at its most predictable, its most carefully regulated by

convention and rules, and yet, because of the stunning dramatic and

improvisational talents of the performers, and because of the

presciently modern gift of the play’s inspiration – Goldoni -

predictability seems to be upended in a breathlessly delightful journey

toward a new shared experience between actors and audience. This

very ancient story is fresh and vibrant once again. The mask is lifted,

and the comedy speaks its timelessness.

|