|

Fantasy has been a component of literature since the earliest folk tales were told around a campfire. (Some would argue that all literature, no matter how "realistic," is fantasy. But most of us would agree that any book that creates a world other than or beyond the everyday world, with elements of magic and myth, is fantasy.) The twentieth century, mired throughout its length in the grimmest of reality, was a fount of literary fantasy; the World War II era alone saw the birth of Middle-Earth, Narnia, and Gormenghast. However much the authors might deny any direct parallels between their fantasy worlds and the political realities of their times, it seems that as reality grows ever more dire, the need to both escape from and interpret that reality through fantasy grows ever greater.

If fantasy is a component of literature, it has been virtually the lifeblood of cinema from the days of Georges Melies's moon voyages and inflatable heads. Certainly most movie cowboys, detectives and pirates bore little resemblance to their real-life counterparts. And today, thanks to the omnipresence of CGI, Middle-Earth and Narnia find life on screen with a vividness their authors could never have imagined (or, perhaps, welcomed).

The cinematic use of fantasy as a direct commentary on society and history is as least as old as Fritz Lang's silent masterpiece, Metropolis. The most famous contemporary practitioner of fantasy-as-satire is Terry Gilliam, though even his greatest films (Brazil, 12 Monkeys) seem more like a succession of brilliant set pieces than a cohesive whole.

All this is prelude to my consideration of Guillermo del Toro's El Laberinto del Fauno (Pan's Labyrinth), which combines dark fantasy and historical tragedy with thematic and dramatic seamlessness. I have never seen any of Del Toro's other films—which include a previous Spanish Civil War-themed fantasy, The Devil's Backbone, as well as the highly personal fantasy Cronos and the Hollywood spectaculars Blade 2 and Hellboy. All I can say is that, after seeing Pan's Labyrinth, I want to fill that gap in my cinematic experience as quickly as possible, for Pan's Labyrinth is a work of genius, a truly great film.

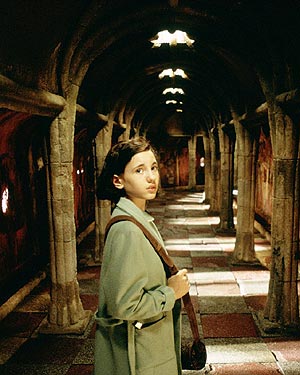

The film begins with Guillermo Navarro's camera swirling through a nightmarish underground landscape, as the narrator tells the sad tale of a lost underworld princess, dying in exile in the outside world, whose soul through many reincarnations seeks a return to her home. It then fades into the scene of Carmen (Ariadna Gil) and her young daughter Ofelia (Ivana Baquero) traveling by military convoy to join Francoist Captain Vidal (Sergi Lopez), Carmen's new husband and Ofelia's stepfather. The year is 1944; as a world war rages outside Spain, the victorious Franco seeks to consolidate his power by rooting out the last of the Republican resistance. None of Franco's soldiers is more dedicated to that cause than Vidal. Carmen is pregnant with Vidal's son, and apparently the pregnancy is a difficult one. It is also apparent that Ofelia is less than happy at the prospect of a reunion with her stepfather. She takes solace in her books of fairy tales, while her mother admonishes her gently to wean herself from them.

During a rest stop, Ofelia finds a curious stone by the roadside. It seems to be an eyepiece fallen from a runestone standing nearby. She replaces it, and a dragonfly immediately buzzes up to her. "Are you a fairy?" she asks it.

From there, Del Toro takes Ofelia on a breakneck tour of two equally horrifying worlds that exist parallel to each other. The dragonfly/fairy takes Ofelia to a menacing, long-abandoned labyrinth near Captain Vidal's encampment, and there introduces her to a faun—not the huggable Tumnus of the Narnia stories, but a glowering, eight-foot monster with twisted horns and a profound contempt for the human creatures of the outside.

The faun informs Ofelia that she is the latest reincarnation of the underground princess, but to reclaim her crown she must perform three tasks, each more difficult and unnerving than the last. As scary as this world is, however, it is a positive comfort compared with the bleak military camp run by Captain Vidal. Vidal is of that type all too pervasive throughout human history: a fanatical, sadistic bully convinced absolutely of his own righteousness. Vidal explicitly believes that truth is revealed only under the extremes of torture, and he treats his family pretty much the same way he treats suspected resistance fighters. He covets his soon-to-be-born son as an extension of his own ego, a new soldier for Franco. Carmen to him is merely the vessel that bears his son, and Ofelia is less than nothing, a recalcitrant recruit to be dealt with as summarily as possible.

The story of Pan's Labyrinth places Ofelia in constant danger as she negotiates the hazards of both worlds. Not surprisingly, the more she succeeds at the tasks the faun sets for her, the more unacceptable she becomes to Vidal. For example, her successful confrontation with the poisonous toad that is destroying the Tree of Life leaves her new party dress drenched in mud, making her unpresentable to the various dignitaries at Vidal's dinner party that night.

The dangers of the parallel worlds accelerate. The sweet, naïve Carmen grows ever frailer and ever less able to protect Ofelia from Vidal, whose depths of cruelty are revealed like successive layers of a particularly rotten onion. (The scenes of torture and brutality in Pan's Labyrinth are as agonizing as any ever put on film.) The faun grows angry with Ofelia for her childish mistakes in completing her tasks. Ofelia's only ally is Mercedes (Maribel Verdu), Vidal's sensible and kindly housekeeper. But Mercedes, who harbors a few secrets of her own, may not be in a position much longer to help Ofelia, or even herself.

Of the many beauties of Pan's Labyrinth, the greatest is the leeway Del Toro gives the audience in interpreting the story's precise meaning. (The one position you're not permitted is sympathy for Franco and his allies, a handicap if you're a conservative Catholic or a reflexive anti-Communist.) You can perceive the fantasy elements as an allegory of Francoist Spain, a meditation on humanity's need for fantasy in the face of grim reality, a commentary on the sad life of a mistreated little girl, or with Tolkienesque literalness (though the unrelieved terrors of the faun's world are unlikely to draw as many obsessive fans as Middle-Earth). Del Toro is deliberately ambiguous in his treatment of the fantasy world: Vidal and the other real-world adults cannot see the faun, but they certainly see the mandrake root the faun gives Ofelia, in one of the film's more important plot twists.

In the same vein, the audience is free to treat the film's ending as apotheosis, as abject tragedy, or as something in between. (One reviewer was so scandalized by the ending of Pan's Labyrinth that—in the service of morality and caveat emptor—he revealed it. Such reviewers should be forced to wear bells around their necks.)

In any case, Pan's Labyrinth is a resplendent masterpiece, its writing, acting, photography, editing, music, and design all flowing seamlessly together. The underworld created by production designer Eugenio Caballero is a mesmerizing amalgam of regal splendor and twisted, murky evil, captured beautifully by Navarro's glowing cinematography. Bernat Villaplana's deft editing shifts us from the forest to the labyrinth in the moment it takes the camera to pass a tree. Javier Navarrete's music underscores and deepens the action without calling undue attention to itself.

All of the film's main performers distinguish themselves. As Ofelia, Ivana Baquero is so real, so natural, and so heartbreaking that you want to rush up onto the screen, rifle in hand, to protect her yourself. As Vidal, Sergi Lopez manages the difficult trick of making Vidal both recognizably human and completely loathsome. Ariadna Gil radiates pathos as Carmen, a woman seemingly resigned to being used up and thrown away, while Maribel Verdu—virtually unrecognizable from her star-making sexpot role in Y tu Mama Tambien—is the film's tower of decent, courageous strength.

Special mention must be made of Doug Jones, a specialist in creature roles and a Del Toro regular. A veteran of everything from McDonald's commercials to M. Night Shyamalan's dismal Lady in the Water, Jones appears not only as the faun, but also as the Pale Man, a saggy, fishbelly-white cannibal who wears his eyes in his hands. The Pale Man qualifies for me as the single most terrifying creature I have ever seen on screen, a rotting homunculus that retains a vestigial human shape but is blanched of all qualities except an endlessly depraved appetite. On the opposite end, the faun—mixing menace with a courtly, chivalrous dignity—is a creation worthy of The Lord of the Rings, or of Jean Cocteau's La Belle et la Bete.

Certainly makeup artists David Marti and Montse Ribe deserve some of the credit for Jones's triumph in these roles, as do costumers Lala Huete and Rocio Redondo. Yet Jones went the extra mile to invest these creatures with life, even learning medieval Spanish to speak the faun's dialogue (though Del Toro, in the end, decided to dub Jones with another actor's voice). The faun and the Pale Man are not just walking costumes, but creatures grounded in their own reality, radiating their own aura. Much of the power of the fantasy elements of Pan's Labyrinth is due to the brilliance of Doug Jones.

|