|

In the spring of 1968, while America writhed in convulsions of fraudulent war abroad and racism, street violence, and assassinations at home, one man, after careful preparation, set off for the solitude and spartan rigors of life in the Alaskan wilderness. Two years prior, Timothy Leary had popularized Marshall McLuhan’s coinage “turn on, tune in, drop out.” This man simply checked out. Or rather, he checked in–with himself.

His name was Richard Louis Proenneke. Perhaps you’re already familiar with this remarkable man, but if not–wow!–do I have a documentary for you. Alone in the Wilderness, produced by Bob Swerer in 2003, beautifully presents Dick Proenneke’s accomplishments as a naturalist, filmmaker, photographer, writer, carpenter, fisherman, woodsman, conservationist, and one very pure human being.

Swerer first met Proenneke in 1986 while filming Alaskan wildlife. After Proenneke died in April 2003, Swerer collated and edited his friend’s superb film footage and synched it with narrated entries from his journals to create a captivating 60-minute biopic chronicling Proenneke’s first year in a remote Alaskan valley called Twin Lakes, a year during part of which he would build by hand his now famous cabin.

You’ve never seen a movie like this one. Alone in the Wilderness is one hour of visual meditation, absolutely soothing, tonic. And it’s a national treasure about a national treasure, a film and a man you will never forget.

The sound of water coursing, a mountain vista to make Ansel Adams swoon, a plucked harp as elegant, subtle soundtrack–the way Bob Swerer begins the film, you feel as though you’ve eased yourself down into a long-overdue hot bath. The sturdy protagonist walks away from the camera toward pines, a pale blue frozen lake, and the screen-filling backdrop of a snow-dappled mountain. The narration begins with one of the great, truly American paragraphs:

It was good to be back in the wilderness again, where everything seems at peace. I was alone, just me and the animals. It was a great feeling: free once more to plan and do as I pleased. Beyond was all around me. My dream was at a dream no longer. I suppose I was here because this was something I had to do–not just dream about it but do it. I suppose, too, I was here to test myself, not that I had never done it before but this time it was to be a more thorough and lasting examination. What was I capable of that I didn’t know yet? Could I truly enjoy my own company for an entire year? And was I equal to everything this wild land could throw at me? I had seen its moods in late spring, summer, and early fall, but what about the winter? Would I love the isolation then, with its bone-stabbing cold, its ghostly silence? At age 51 I intended to find out.

One can hear more than just a faint echo of Henry David Thoreau’s famed explanation for his 3-year residency alongside Walden Pond: “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”

In many ways, Proenneke resembles his philosophical and practical forefather in New England. Thoreau may not have been quite the woodworker Proenneke was, but he was no mean carpenter, hand-crafting his house and, like Proenneke, hauling a good deal of the materials on his back.

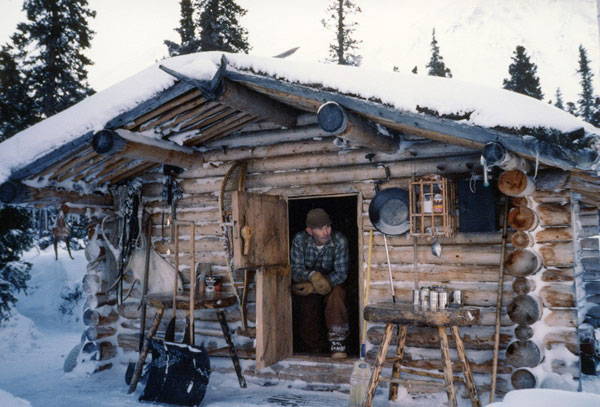

Each man’s cabin was about the same size: Thoreau’s measured ten feet wide by fifteen feet long, Proenneke’s a foot wider. Both men equipped their homes with a fireplace, but Thoreau bought bricks while Proenneke gathered hundreds of stones. Thoreau uses “mostly shanty boards.” Proenneke fells trees to fabricate his own lumber. Thoreau seems more interested in thrift, proudly providing his reader an itemized cost of his cabin (it totaled $28 and 12.5 cents.) Even over a century later, Proenneke probably beat Thoreau on costs, but his chief pleasure came from craftsmanship itself.

Both men kept a garden and both proved keen-eyed, meticulous naturalists. And like Thoreau, Proenneke built his house by the shores of a body of fresh water which provided that single most necessary resource, as well as fish and a breathtaking vista. Thoreau had Walden Pond, Proenneke Twin Lakes.

Like many others, my introduction to Richard Proenneke came by way of watching Alone in the Wilderness on my local Public Broadcasting Service channel. They were doing their fundraising campaign and said that this documentary had become their most-watched, most-requested program. I quickly discovered why.

Initially, I was drawn in by the astonishing carpentry display–the skill in those hands, the ingenuity, the Zen master ease with which this man took trees and transformed them into anything he chose! As I continued to watch, I realized Dick Proenneke possessed manifold talents, but underlying them all was his great calm.

If he was anything, he was methodical. He never seems to be in a rush. He takes the time to think, to plan. For one, the stakes are extremely high, much higher than they might’ve been for Thoreau. With no disrespect to Massachusetts winters, Twin Lakes sits 100 miles southwest of Anchorage. Walden Pond is a mile and a half’s walk from Concord. And no matter how far he roamed, Thoreau never had to worry about running into a 900-pound brown bear or a pack of hungry wolves….

But Proenneke seems to have always been a patient, contemplative man. He enlisted in the Navy just after the Pearl Harbor attack, serving as a carpenter. Maybe it was there that he was introduced to a different saw, an old military slogan called The 5Ps: Proper Preparation Prevents Piss-poor Performance. After the war, he learned a new, fairly lucrative trade by going to diesel mechanic’s school. Over the years, he’d use these skills, as well as stints as a salmon fisherman, to save for a unique retirement.

Part and parcel of his calm approach to life, after he retired in the spring of 1967, he spent the summer scouting out the Twin Lakes area for the ideal spot to build his cabin. He even cut down a batch of trees which he’d use for its construction: “I had harvested the logs from a stand of spruce less than 300 yards from where they were now piled.”

An 11’x15’ cabin might sound like tight quarters, but outside his Dutch door extends the practically endless Alaskan wilderness into which Proenneke happily ventured even when the mercury measured 40 degrees below zero. And that’s Fahrenheit.

As I’ve explained to people, you have to remind yourself that the man doing all these wonderful things in the documentary is the man who filmed the documentary! And for those who might wonder, he used a Bolex 16mm wind-up camera for film footage and an Exakta VX IIb 35mm camera for still photos (the latter was generously donated to Lake Clark’s Proenneke museum collection by Dick’s brother Raymond in 2009.)

Dick Proenneke dwelt in long periods of solitude, not self-isolation. That solitude, that quiet, that calm allowed for introspection, as well reflection on even the most mundane things. He arrived at many of the same conclusions rare others like him did. At one point in Alone in the Wilderness, we watch Proenneke make his front door. After crafting a gorgeous set of four wooden hinges and an ingenious door lock–easy to open by hand but one that would stymie a nosy bear, Proenneke reflects: “Too many men work on parts of things. Doing a job to completion satisfies me.”

Or there’s the evolution of his stance on hunting. During the entire year chronicled in Alone in the Wilderness, Proenneke shoots exactly one animal, a Dall’s sheep. Like everything else, he does it with precision and economy. As he wrote in his journal: “I opened and closed the season with one shot. The search for meat is over. I hated to see the big ram end like this but I suppose he could have died a lot harder than he did.”

Nor does does he film the the kill, only how he cleans the large white pelt and smokes the meat of the animal. No further comment is made, but over 30 years’ worth of subsequent journal entries, as well as conversations and “exchanges” with friends and others reveal that he disdained the cruel waste of so-called sport hunters. He ceased his already minimal subsistence hunting by 1978. He remained happy to dine on meat when he found it, such as fresh wolf kills of caribou or moose. His diet was mainly a mix of fish, wild berries, vegetables, and the groceries his friend the bush pilot Leon “Babe” Alsworth brought in, such as oatmeal, sourdough (for his beloved hot cakes), bacon, eggs, and beans.

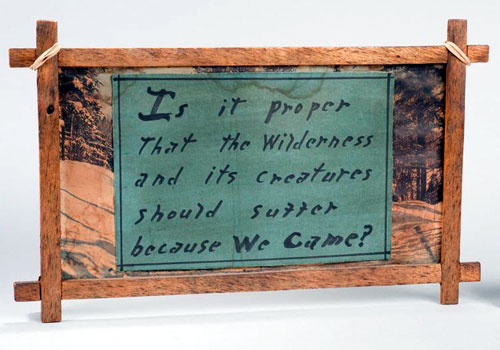

A beautifully crafted sign for a motto which Proenneke wrote, framed, and hung in his cabin says it all: Is it proper that the Wilderness and its creatures should suffer because We Came?

I want to stress that Richard Proenneke was no recluse or hermit; to call him such is to completely misunderstand him. Dick welcomed visitors, however infrequent they may have been early on. He regularly corresponded with his brother “Jake.” He worked in various capacities for the National Park Service. Perhaps most tellingly, he happily collaborated with the NPS in 1977 in making a documentary on himself, One Man’s Alaska. When Twin Lakes started to see more tourism in the late 1980s and early 90s, Dick embraced his role as a Volunteer-in-Park, supremely qualified to greet and assist visitors. And he always answered fan mail as his legend quietly grew.

When you’ve almost finished watching Alone in the Wilderness you’re tempted to think “what an accomplishment to do all those things and live like that for a year” –as if the story ended there. Perhaps you’ve figured out that Dick Proenneke did a little more. In an epilogue to truly take your breath away, you learn that he spent the next 30 years living in his cabin alongside Twin Lakes, carefully recording the cycles of life.

He didn’t go “off the grid,” he was never on it. He didn’t survive in nature, he became a part of it. Richard Proenneke found that solitude is a path to freedom.

Additional Resources:

National Park Service

At the end of his life, Proenneke donated his cabin to the National Park Service. It and all its contents comprise a treasured piece of Lake Clark National Park & Preserve.

Richard L. Proenneke

https://www.nps.gov/lacl/learn/historyculture/proenneke-and-wilderness.htm

The National Park Service has a wonderful set of Web pages with extensive resources to explore Dick Proenneke’s legacy, including excerpts from (and illuminating commentary on) his 30-plus years of journal writing; a virtual tour of his cabin; and a collection of his photos. Perhaps the most satisfying item in the online museum collection is the 27-minute documentary the NPS made about Proenneke in 1977, One Man’s Alaska.

As Bob Swerer would later do more extensively in his own documentary, the NPS used Proenneke’s film footage, photos, and journal entries. Along with segments of film–some endearing, some quietly astonishing–which do do not appear in Alone in the Wilderness, One Man’s Alaska features Proenneke’s actual voice both in interview portions and for a good part of the film’s narration.

|