|

Too

often

I

find

myself

writing

an

essay

in

which

I

heap

posthumous

praise

on

someone

I've

admired:

my

heartfelt

farewell

to

Hall

of

Fame

pitcher

Tom

Seaver,

"Saying

Good-bye

to

a

Boyhood

Hero,"

or

"Tom

Petty:

A

Charmed

Rock

'n'

Roll

Life,"

where

I

delve

into

an

American

cultural

treasure

and

personal

touchstone.

Now it's July and that means the Tour de France, so I want to celebrate a hero of mine who is still with us, one of our country's greatest athletes, a titan of cycling, a paragon of integrity, and, by all accounts, a stand-up guy: Greg LeMond.

I'm not the only one.

There's a new film about LeMond, The Last Rider,

directed

by

Alex

Holmes.

The

documentary,

playing

in

select

theaters

around

the

U.S.

this

month,

focuses

on

LeMond's

long

road

to

victory

in

the

1989

Tour

de

France

after

a

near-fatal

hunting

accident

in

1987.

Like

Hollywood,

the

sports

world

loves

a

comeback

story;

LeMond's

remains

one

for

the

ages.

In a statement, director Alex Holmes said: "The Last Rider is a celebration not just of athletic talent but of the power of love to enable us to realize our potential, and sometimes even to achieve that which the world thinks is impossible."

Yes, a celebration!

Greg's

story

is

worth

celebrating.

It

teaches

and

inspires.

(Born

June

26,

1961,

he

celebrated

his

62nd

birthday

last

month:

happy

birthday,

Greg!)

The Last Rider inevitably competes with the ESPN Films 30 for 30 classic, Slaying the Badger,

a

biopic

which

premiered

in

July

2014

and

is

easily

one

of

the

best

sports

docs

ever

made,

a must-watch.

ESPN's

film

took

a

different

angle;

its

title

refers

to

Frenchman

Bernard

Hinault,

the

tenacious

5-time

Tour

de

France

winner

nicknamed

"The

Badger"

whom

LeMond

beat

to

win

his

first

Tour

in

1986.

It

was

far

more

complicated

than

that,

though:

Hinault

and

LeMond

were

teammates

and

close

friends.

This

new

film's

title

speaks

to

the

fact

that

Greg

LeMond

remains

the

only

American

to

win

the

Tour

de

France

(subsequent

American

winners

Lance

Armstrong

and

Floyd

Landis

were

stripped

of

their

titles

when

it

was

found

that

they

were

drug-cheats.)

Greg

may

be

the

last

rider

to

have

won

the

Tour

clean,

but

more

on

that

later.

Unlike

our

home-grown

sports,

cycling

may

not

be

familiar

to

many

American

readers.

In

the

early

20th

century,

America

had

a

thriving,

well-moneyed

velodrome

racing

circuit.

Wintertime

crowds

packed

indoor

tracks

in

Chicago,

Detroit,

Minneapolis,

Newark,

and,

most

of

all,

New

York's

Madison

Square

Garden.

But

the

sport

vanished

after

World

War

II,

replaced

by

football

and

basketball.

And the French, Belgians, and Italians owned road-racing. Greg was a pioneer. When he won the Tour de France in 1986, he wasn't just the first American to do so, he was the first non-European winner. Let me offer a few insights into the sport to convey the greatness of Greg LeMond's achievements.

There

are

many

kinds

of

road

races,

some

take

a

day,

some

weeks.

In

a

time-trial,

each

rider

heads

off

individually

against

the

clock,

but

in

many

races,

especially

big

multi-day

tours,

riders

compete

as

a

team.

Strategy

abounds

and

I

could

write

a

treatise

on

the

complexities

of

squad

composition

or

the

sometime

alliances

struck

between

rivals.

Most

important

to

understand

is

that

due

to

aerodynamics,

cyclists

in

a

group

move

much

faster

than

lone

riders.

The

main

group,

called

the

peloton,

can

sustain

astonishing

speeds,

in

part

because

the

riders

rotate

the

work

of

leading,

where

wind

resistance

is

greatest.

That's

why

the

peloton

usually

catches

a

breakaway.

Relatedly,

each

team

has

its

leader,

its

best

rider

for

whom

the

others

work,

i.e.

the

leader

will

draft

behind

his

"lead-out"

teammates,

thereby

saving

his

legs

for

decisive

attacks.

That's

the

way

it's supposed to work.

The

Tour

de

France,

or

simply

"the

Tour,"

is

one

of

cycling's

three

so-called

Grand

Tours,

the

others

being

the

Giro

d'Italia

and

the

Vuelta

a

Espa帽a.

Each

entails

21

days

of

cycling,

known

as

stages—three

weeks

of

racing

with

rest

days

on

two

Mondays.

The

Tour

covers

about

2,100

miles,

which

averages

out

to

a

tidy

100

miles

of

pedaling

per

day,

but

some

stages

are

far

longer,

as

much

as

140

miles.

Now,

I

don't

know

how

much

cycling

you've

done,

but

100

miles

is

a

daunting

distance;

even

at

a

leisurely

pace

over

gentle

topography

with

coffee

breaks

and

a

stop

for

lunch,

a

century,

as

cyclists

call

it,

makes

for

a

very

long

day

in

the

saddle.

Try

hammering non-stop against your rivals as you traverse endless switchbacks up and over the Pyrenees or Alps!

And it's not just how far but how fast the riders go. Since 2007, the winner's average speed over the Tour's 2,100 miles has been just under 25 miles per hour. Get on your Schwinn or your $5,000 carbon-fiber road bike and try to maintain 25 mph for 30 minutes then tell me how you feel.

From

the

outset,

Greg

LeMond

was

a

winner.

But

at

every

third

or

fourth

step

in

his

career,

adversity

beyond

his

control

thwarted

him.

As

a

15

year-old

brand

new

to

the

sport,

he

won

the

first

11

races

he

entered.

He

won

the

American

National

Junior

Road

Race

Championship

in

1977

and

the

UCI

Junior

World

Road

Race

in

1979.

When

he

was

selected

for

the

U.S.

Olympic

team

at

18

he

was

the

youngest

cyclist

ever

to

make

the

squad,

but

America's

pointless

boycott

of

the

1980

Olympics

snuffed

his

chance

to

make

history.

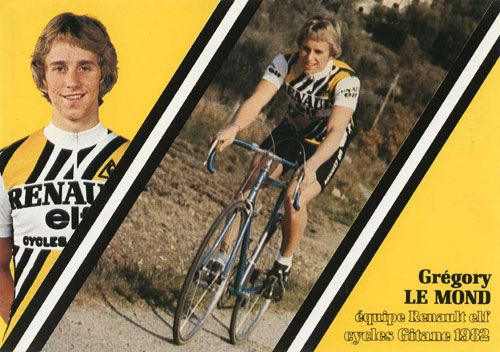

In 1981, LeMond turned pro and immediately turned heads. The French

press loved this talented American who quickly learned to converse in their

language. In 1983 he won the UCI Road World Championship, a one-day

race which measured 167 miles that year. At 22 he was the best cyclist on

the planet.

In his first Tour de France, in 1984, he finished third, donning the white

jersey for the young rider classification, recognition for the best debut. The

next year he could have won the Tour but, without giving away the intrigue

of Slaying the Badger, that rule about a team riding in support of its

strongest cyclist was brazenly ignored. So he made history by winning the

1986 Tour.

Then, while out hunting in 1987, his brother-in-law mistook him for a

quarry and blasted him with a shotgun, perforating his neck, lung, heart,

and liver with 60 lead pellets. Doctors said LeMond was 20 minutes from

death, having lost 65% of his blood. Lodged in spots too dangerous to

operate, such as the lining of his heart, 35 of those lead pellets remain in

his body, slowly poisoning him.

Overcoming his harrowing ordeal and the attendant havoc it wreaked on

his fitness, LeMond returned in 1989 to re-conquer Paris (and the rest of

France.) Even though you know he wins the '89 Tour it doesn't spoil

anything, because it's how he wins which will thrill you.

Coasting from his Tour triumph in July, Greg rode to victory a second time

at the UCI Road World Championship in August. And then he won the

greatest road race of them all a third time in 1990, hoisting the winner's

trophy over his head atop the podium in Paris!

The 35 shotgun pellets in LeMond's body hastened his retirement. Initially,

his youth and superb cardiovascular shape enabled him to return to

winning form, but, then as now, the harder he exerts himself the more

those insidious projectiles titrate lead into his system. But something else

forced Greg to call it quits, another adversity beyond his control which

thwarted him.

Shortly after he returned to cycling to regain its summit, a seismic shift

rumbled through the peloton; by the early 1990s, the average rider's power

output, measured in watts, jumped—massively. Riders previously at the

bottom of the standings were now generating as many watts as the winners

on past stages. What happened? Superior nutrition? New insights into

training?

EPO had hit the streets—a synthetic version of the hormone erythropoietin

developed for anemia patients in order to stimulate red blood cell

production. It was a crazy time in cycling. Riders like Marco Pantani, Jan

Ulrich, Bjarne Riis, Alberto Contador, and, of course, Lance Armstrong

smashed course records—when they weren't dying in their sleep. Since it

was all done in secret, no one knew exactly how much EPO to take. The

cyclists were guinea pigs.

Elite endurance athletes have astonishingly low resting heart rates; when

their blood became too dense with red blood cells, their hearts simply

stopped in deep sleep. Doping cyclists now set their alarms for 3 AM,

hammered an hour on a stationary bike to get the blood flowing, and then

went back to sleep! Hmm, dozens of healthy young riders mysteriously

dying in their sleep….

Meanwhile, Greg returned to defend his Tour de France title in the best

shape of his life and was dropped . . . by the peloton. It was the beginning

of the doping era and almost every subsequent Tour winner would be

tainted, disqualified, banned, or all of the above.

Even before he retired, LeMond courageously went on record against

performance-enhancing drugs in cycling. He was rocking a very big, very

lucrative boat. His outspoken warnings cost him dearly, especially when he

called out Lance Armstrong's massive fraud in 2001. A vindictive monster

by anyone's definition, Armstrong set about to methodically destroy

LeMond and his business interests, particularly Greg's successful

partnership with Trek Bicycle Corporation who had manufactured LeMond

Bicycles since 1995. Trek also sponsored Armstrong, then a media

-dominating darling and money machine for his backers. The sinister

Texan used his leverage to get Trek to sever ties with LeMond. Along with

much of the press, the zombie Pharmstrong cultists pilloried LeMond in

every online forum (these were people who knew as much about cycling as

I do about double-entry accounting—no, actually less since I can perform

basic arithmetic.)

Along with his opposition to performance-enhancing drugs, LeMond also

warned the cycling community quite early in the game about mechanical

doping—the use of tiny electric motors hidden inside bike frames. Once

again, Greg took a ton of abuse, his critics leveling the usual anonymous

complaints—"he's just a hater"—until female Belgian cyclist Femke Van

den Driessche had a problem with her bike at the 2016 UCI Cyclo-cross

World Championship and officials noticed electrical wires hanging from

the frame. Now how did a motor get inside my bike? Oops..

I first became dimly aware of professional cycling and its then-only

American star, Greg LeMond, in my senior year of high school. That was

1984. I began riding a metallic blue Fuji "Sports 10" which I bought from a

friend and proceeded to modify until it resembled a true road bike (to

include ditching the shift levers on the handlebar stem and installing

Shimano levers on the frame's downtube, as well as buying a pair of

chromalloy pedals and shiny stainless steel toe clips.) On summer

Saturdays I often rode the hour it took me to pedal from my house in

Valley Stream to my pal Mark's house in bucolic Muttontown, a beloved

odyssey of my youth.

Since that happy day I brought it home in July 2017 from an eBay seller in

Connecticut, I've been riding a 1996 LeMond Bicycles Tourmalet, so named

for the fearsome Pyrenees mountain pass, the Col du Tourmalet, where

Greg attacked in 1990 to make up 5 minutes on race leader Claudio

Chiappucci, thereby sealing his third Tour de France victory. It's a steel

-frame bike exquisitely painted in a delicious red. Today's feather-light

carbon-fiber frames make it seem 'Old School." A less generous description

might be "heavy dinosaur," but it's a joy to ride—comfortable, smooth,

dependable, and light-years better than my old Fuji. When I'm not

powering it over the rolling hills of central New Jersey, I keep it in my

living room so I can ogle its classic lines, its cheerful colors emblazoned

with my hero's name and the World Champion's rainbow stripes.

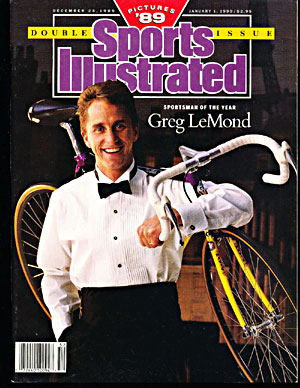

Framed on one of my walls is a copy of the December 25, 1989 issue of Sports Illustrated with Greg LeMond on the cover in bowtie and tux sans

jacket, his bike jauntily slung over his left shoulder as he beams the

winning smile of Sportsman of the Year. More inspiration, more

celebration.

Cycling's doping-stained history has sadly vindicated LeMond. In the light

of what we always knew, as well as revelations in hindsight, his

achievements look more and more impressive. It hasn't been an easy road

for Greg LeMond, but he has always ridden it with integrity and class. He's

been one of my heroes for a long time. Still is. His life is worth celebrating.

|