|

It

is

a

profound

and

necessary

truth

that

the

deep

things

in

science

are

not

found

because

they

are

useful;

they

are

found

because

it

was

possible

to

find

them."

—J. Robert Oppenheimer

And

what's

this?

"I

am

become

Death,

the

destroyer

of

worlds."

It

is

an

ancient

Hindu

text

quoted

by

an

American.

An American?

He invented the atomic bomb and he was later accused of being a Communist.

—dialogue between Soviet Political Officer Putin and Captain Marko Ramius, The Hunt for Red October

How can I save my little boy

From Oppenheimer's deadly toy?

—Sting, "Russians"

The other night I watched Oppenheimer on the big screen, reclining in the air-conditioned dark of a New Jersey movie theater just a few miles up the

road from Princeton, that ivied hive of physicists and mathematicians

where much of the film takes place.

Like its protagonist and the developments he oversaw as director of The

Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory, the film Oppenheimer

achieves its colossal ambition. Christopher Nolan, who directed the picture,

wrote the screenplay by adapting the 2005 biography American

Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer, a book

which took its authors, Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherman, 25 years to

complete. The movie clocks in at exactly three hours.

I've yet to read American Prometheus but back in 2009 I read The Making

of the Atomic Bomb by Richard Rhodes, a riveting 788-page tome

published in 1986 still considered the subject's definitive account: so much

of that book came back to me as I watched Oppenheimer.

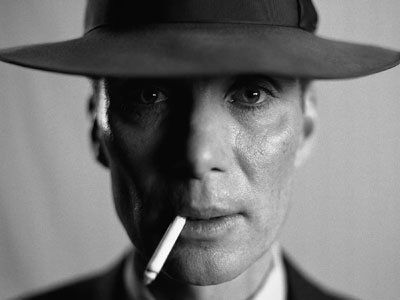

From its fidelity to the facts to its curious and surprising narratorial

framework, from its inspired casting to the superb performances those

players give, Oppenheimer excels in every way. And Cillian Murphy's

portrayal in the title role tops the film's achievements. Murphy began

studying law in his hometown at University College Cork in Ireland but had

the wisdom to fail his first-year exams and take up acting. We can all be

thankful: like Robert Downey Jr. in Chaplin, Oppenheimer was a destiny

role for Murphy. It's a lovely coincidence that Downey figures prominently

in the picture.

It's a great film. And as such, it continues to make me think long after the

credits rolled. I've been thinking about Oppenheimer, this immensely

complex mind and also just an ordinary man with wants and needs. I've

been re-appreciating the awe-inspiring, altogether Herculean task of

building an atomic bomb so rapidly. And I've been thinking about the

fallout, the nuclear legacy, the proliferation of world-ending weapons and

whether it was all worth it.

In a recent interview, Christopher Nolan declared that J. Robert

Oppenheimer is the most important person in human history. To riff on

quantum mechanics, he's probably not wrong.

From time to time, someone comes along who influences a continent or

two with an idea, an invention, or a lie. Whoever fashioned the first plough

ushered in civilization as we know it. A handful of neurotics wandering the

deserts of the Near East managed to spread variations of the same misery

to most of the globe. Edison's bulb has brought light to the world. But

Oppenheimer, so-called "Father of the Atomic Bomb," supervised the

creation of a technology which can extinguish civilization—every light and

life, neurotic or otherwise, on the planet—with the push of an index finger.

Referencing the title of the book on which it's based, Oppenheimer begins

with two captions in sequence:

Prometheus stole fire from the gods and gave it to man.

For this, he was chained to a rock and tortured for eternity.

Very poetic, fairly apt, but I don't think you can hang "the blame"—if that's

what it is—solely on Oppenheimer. Just as an enriched uranium pile

reaches critical mass, physicists and their insights into nuclear theory

reached a kind of critical mass in the early 20th century. Global war

provided a catalyst to hasten the process, but the atom was getting split,

one way or the other.

Oppenheimer's uncanny mental powers enabled him to transmute

abstractions of theory—chalk scribbles on blackboards and rarefied

conjectures—into the unleashing of fundamental forces. Still, for all his

genius, he needed practical help. The point is made several times in the

movie that Oppy wasn't too swift around beakers and Bunsen burners.

Enter General Leslie Groves, played with aplomb and accurate

brusqueness by Matt Damon. As historian David M. Kennedy suavely states

in The American People in World War II:

It is easy to see Professor Oppenheimer and General Groves as foils for

one another—the gaunt, soul-tortured scientist, melancholic child of

the Jewish diaspora, sensitive reader of Sanskrit epics and T. S. Eliot's

poetry, the brooding genius who orchestrated all the savants gathered

at Los Alamos, playing the tragic hero opposite Groves' corpulent

Rotarian Babbitt, West Point engineer, career soldier, gruff maker of

buildings and bombs and a man without scruple, delicacy, or

conscience. But if Oppenheimer and his scientists at Los Alamos

constituted a crucial American asset in the race to build the bomb,

Groves also embodies a kind of genius—the peculiarly American genius

for organization and management and for thinking in terms of

stunningly vast enterprises.

Indeed, before Groves was given the task of arranging logistics for The

Manhattan Project, he built the Pentagon.

Even a 3-hour epic film can't do justice to the story of the making of the

atom bomb; it is the story of World War II itself, packed with all the

conflict's major themes: the clash of rival ideologies; national economies

pitted against each other; and, relatedly, the development and impact of

technological innovations, such as RADAR, cryptography, and the A-bomb

itself.

Once again, here's David M. Kennedy's succinct take:

The bombs were the singular achievement of the age. It was no

accident that they were made in America, and only in America. Indeed,

the tale of the bombs' making braids together into one plot so many

strands of the era's history that it might be taken as the greatest war

story of them all, the single most instructive account of how and

perhaps even why the conflict was fought and the way the Americans

won it.

In 1939, the great Danish Nobel laureate in physics Niels Bohr correctly

surmised: "It would take the entire efforts of a country to make a bomb.

[I]t can never be done unless you turn the United States into one huge

factory."

That's practically what happened under General Groves' leadership.

America bankrolled The Manhattan Project with more than $2 billion

(those are 1942-45 dollars) and employed 150,000 people. The Oak Ridge

gaseous-diffusion plant in Tennessee covered 59,000 acres; the building

housing the diffusion tanks took up 42 acres alone! As Kennedy writes, the

Hanford plant on the banks of Washington's Columbia River used

electricity from the New Deal's Bonneville and Grand Coulee dams to

power four cavernous uranium separation plants—"workers tortuously

squeezed out plutonium from grudging nature, a dime-size pellet from

every two tons of uranium."

Kennedy offers another astonishing perspective: "In the space of three

years, Groves had erected out of nothing a vast industrial complex, as large

in scale as the entire prewar automobile industry." On touring these mini

-cities in 1944, Niels Bohr declared in the matter-of-fact way only a lofty

physicist could: "You see, I told you it couldn't be done without turning the

whole country into a factory. You have done just that."

One phrase you hear over and over is "the race to build the bomb." It

makes for drama. Certainly the scientists at Los Alamos feared that their

German rivals might get there first. As it turns out, there was no race at all.

Albert Speer, Germany's armaments minister, wrote after the war that by

the autumn of 1942 they had "scuttled the project to develop an atom

bomb" based on overwhelming logistical demands. He also added that "our

failure to pursue the possibilities of atomic warfare can be partly traced to

ideological reasons. . . . To his table companions Hitler occasionally

referred to nuclear physics as 'Jewish physics.'"

There's a scene in the movie where Groves worries that the Germans have

a head-start. They do, Oppenheimer tells him, but the Allies have an

advantage: antisemitism. Aside from impossibly large financial and

logistical requirements, Hitler's policies methodically purged Germany of

the minds with which to design and build an atomic bomb, indirectly

sending many of them to England and America. An astonishing number of

Los Alamos scientists, engineers, and technicians (many of them recent

refugees) claimed Jewish ancestry, including Hans Bethe, Felix Bloch,

Niels Bohr, Richard Feynman, Otto Frisch, Hans Halban, Rudolf Peierls,

Joseph Rotblatt, Franz Eugen Simon, Leo Szilard, Edward Teller, Stanislav

Ulam, John von Neuman, Eugene Wigner, and, of course, Oppenheimer.

(While Italian himself, Enrico Fermi fled Fascist Italy because they had

passed the anti-Semitic Racial Laws which threatened his wife Laura, who

was Jewish.)

As with this viewer, what audiences will likely think about most after

seeing Oppenheimer is the actual use of two atomic bombs. Far more

disturbing but less visceral than mushroom clouds is the subsequent

proliferation of atomic weapons among a handful of nations (innocuously

called The Nuclear Club, those countries now comprise France, India,

Israel, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United

States.)

Ostensibly, what motivates people to question the dropping of atomic

bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki is concern for human life, an admirable

consideration. As with any matter of consequence, one strives to make an informed decision. To do that, you need the facts. But there's something

else which informs one's judgment: experience. I went back and re-read

Paul Fussell's essay, Thank God for the Atom Bomb, originally published in

August 1981. Yes, it's a provocative title but not his coinage (Fussell drew

the phrase from a passage in William Manchester's memoir of fighting in

the Pacific, Goodbye Darkness.) I urge you to read this classic essay by one

of America's most eloquent and deeply humane writers.

And don't let the title mislead you: Fussell was no war-monger. He was,

however, that voice so rare nowadays, an accomplished literary scholar,

critic, and writer (his The Great War and Modern Memory won the National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award) who

saw combat. As he explains in his essay, when the atom bombs ended the

war, he was a 21 year-old second lieutenant, a rifle platoon leader in the

45th Infantry Division in Europe. He'd seen fierce combat; while deemed

fit for more of it, he'd already been wounded in the back and leg. Despite a

lifetime's worth of war against the Germans, Lt. Fussell was getting ready

to ship out to the Pacific. He and his unit would be rushing up the beaches,

Normandy-like, on Honshu near Tokyo as part of Operation Olympic, the

invasion of Japan's home islands. (As he points out, an earlier landing on

Kyushu would be carried out by the 700,000 American infantrymen

already in the Pacific.)

One might be led to believe that we've gained perspective with the passage

of time, but, apropos the wise points Fussell makes in his essay, I'd argue

we've lost perspective. But first the facts with their cruel but

overwhelmingly convincing calculus of why using the atom bomb was the

right call:

The battle for Okinawa, the smallest, least populated of Japan's five main

islands, raged from April 1-June 22, 1945. The losses beggar belief: 50,000

Allied casualties of whom about 12,500 were killed; 110,000 Japanese killed (fewer than 8,000 surrendered); according to local authorities, at

least 149,425 Okinawans were killed, died by coerced suicide, or went

missing. Now understand: the Japanese had two divisions on

Okinawa—they had 20 on Kyushu and Honshu. Based on those numbers,

Colonel Andrew Goodpaster of the War Department estimated American

casualties for Operation Olympic might reach half a million.

The British intended to invade Malaya on September 9 with six divisions

(roughly 200,000 men or the same size force that landed at Normandy)

with the intent of liberating Singapore. They expected fighting to last

through March 1946—seven months of more savagery.

In the summer of 1945, Japanese Marshal Terauchi issued an order that

upon Allied invasion of the home islands, all prisoners of war were to be

executed by their camp commanders.

Documents obtained after the war give no indication that Japan had any

intention of suing for peace before the dropping of the atomic bombs.

While Emperor Hirohito exercised taciturn caution, the cabal of generals

led by the hyper-fanatical War Minister Korechika Anami actually looked

forward to an Allied invasion and an "honor-satisfying bloodbath," a mania

summed up by a Japanese Army spokesman in early 1945: "Since the

retreat from Guadalcanal, the Army has had little opportunity to engage

the enemy in land battles. But when we meet in Japan proper, our Army

will demonstrate its invincible superiority." Madness! Anami urged an all

-out, national kamikaze attack on the Allies even after A-bombs fell on

Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Ultimately, he obeyed his emperor, refusing to

participate in an attempted military coup the night before Hirohito was to

broadcast a recording of Japan's acceptance of surrender. On the morning

of August 15, 1945, before that famous broadcast aired, Anami committed

ritual suicide.

In "Counting the Dead at Hiroshima and Nagasaki" in Bulletin of the

Atomic Scientists, Alex Wellerstein provides a fine, well-researched

analysis of why there are considerable disparities in casualty estimates and

no way to know for sure. He suggests a thoughtful bracketing of both

numbers and agendas: the American military estimated around 70,000

people died at Hiroshima, while later independent estimates place that

number at closer to 140,000; in both estimates, the majority of deaths

happened on the day of the bombing with nearly all deaths taking place by

the end of 1945.

On the night of March 9-10, 1945, the US Air Force firebombed Tokyo,

dropping incendiary bombs filled with napalm knowing that most of the

city's structures were made of wood and bamboo. The ensuing firestorm

drew cool air from the suburbs inward, turning the city into a furnace:

ambient temperatures reached 1,800℉; clothing ignited spontaneously;

asphyxiation killed thousands as fire gobbled up oxygen; thousands

drowned or were boiled alive when they tried to shelter in the city's canals,

pools, or rivers. The smell of burning flesh reached B-29 crews as they

circled Tokyo at 5,000-7,000 feet to drop their bombs. Estimates vary, but

it's safe to say that the raid killed over 100,000 Japanese, mainly civilians;

one million were left homeless. Operation Meetinghouse, as the raid was

called, lasted 2 hours 40 minutes and was the single deadliest, most

destructive air attack in history.

I submit to you that it's no more humane to incinerate civilians with

napalm than with a nuclear blast.

Operation Olympic and the planned British invasion of Malaya would have

made Iwo Jima and Okinawa look like schoolyard tussles. The bloodbath

would have been appalling, even to an Allied public callused by years of

casualty reports and those dreaded telegrams from the War Department.

The atom bomb saved millions of Japanese lives—lest one think it's

somehow biased to reckon the merits of using the bomb only in terms of

American lives saved. And it is completely fair, by the way: those million

-plus American and Commonwealth soldiers preparing for the invasion

had as much a right to return to their families and live out their lives as any

Japanese civilian or combatant.

Paul Fussell argues in his essay: "The degree to which Americans register

shock and extraordinary shame about the Hiroshima bomb correlates

closely with lack of information about the Pacific war." It also correlates to

lack of experience. A finite number of men fought against the Japanese in

World War II. They're almost all gone now. But we can gain their

experience secondhand. Another way to understand the bitter necessity of

using the atom bomb would be to read E. B. Sledge's With the Old Breed at

Peleliu and Okinawa, a book Fussell cites in his essay and considered the

finest combat memoir of the war.

Sledge and his buddies intentionally flunked out of college to enlist in the

Marine Corps so they wouldn't miss out on the fighting. They got got more

than they bargained for. With the Old Breed is a book you will never forget,

one written by a deeply good man who struggled for years with the war's

horrors. Part of his problem was his inability to develop the mental callus

with which to insulate himself from the daily brutality. His other problem

was to find himself knee-deep in what many historians regard as the most

savage human combat ever waged. His book is a touchstone text in the

2007 Ken Burns and Lynn Novick documentary The War, as well as one of

the two memoirs on which the 2010 HBO mini-series The Pacific was

based.

I think With the Old Breed should be required reading for every American

kid at some point in their high school or college curriculum. If you want to

understand why a soldier would say "thank God for the atom bomb"—and

why he'd be right, read Sledge's book. Or as another eminent American

historian, Stephen Ambrose, titled his succinct Op-Ed in The New York

Times in August 1995—The Bomb: It Was Death or More Death.

Which returns us to Oppenheimer. As he watched the culmination of his

handiwork unfold in Trinity, the test detonation of the first atomic weapon

on July 16, 1945, Oppenheimer thought of the line from the 700 year-old

Sanskrit epic, the Bhagavad Gita: "Now I am become Death, the destroyer

of worlds." A haunted man, Oppenheimer soon became a hunted one, a

national hero belittled, attacked, and interrogated by a bunch of grocery

clerks. A savior to hundreds of thousands of Allied troops, but none of

them were in a position to save him.

It's difficult to imagine the complex emotions Oppenheimer experienced:

what if you were the one who uncorked the nuclear genie from the bottle?

Perhaps he wanted to be a martyr. He was many things but for all his

brooding he didn't "become Death," that's a pair of shoes nobody's feet are

big enough to fill. The atom bomb would be made, with or without

Oppenheimer, because it could be made; in that endeavor he was merely

an instrument of a necessary truth.

|