|

Prologue

Okay. The Catch-22 is that in order to get a screenplay read and considered, you have to know someone in the business. But to know someone in the business, you sort of have to have a track record as a screenwriter which is difficult to do if you haven't had anyone read your screenplay because you don't really know anyone....

Thus, festivals: the way in for people who don't have a way in.

The Script

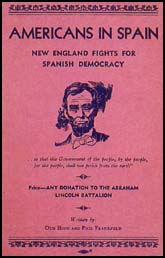

|

The Abraham Lincoln Brigade eventually had 3000 men and women serve in Spain.

|

|

To get some traction on a screenplay I really liked, I began submitting Ain't Ethiopia, which I had written during my final semester at NYU in 2004. It combines two of my enduring interests. The first is the continued rippling out of America's racial history in our culture. I use "rippling out" in this sense: scientists can still detect the corrugations in space-time caused by the Big Bang 13 billion years ago, and so it is with slavery, America's Big Bang. A current canard concerns how Hurricane Katrina exposed the barely hidden underbelly of America's racial indifference, a comment often made and dismissed in the same breath by the punditocracy, as if to say, "Oh, that kind of attitude is so old-school! Get past it!" Yet those pictures of the Superdome and convention center exist they mutely document, they accuse by simple demonstration. They are the photographic evidence of the scores gouged by that explosion. They cannot be planed down by cavalier dismissal.

|

Oliver Law, the first black American to command white troops. He appears in Ain't Ethiopia.

|

|

The second is the Spanish Civil War, a conflict that has always fascinated me in how it hooked the minds and bodies of people whom one would think would have no interest in carnage and destruction in the case of my script, a poor young barely educated black man from Mississippi escaping from the people who lynched his wife because they believed her a Communist for asking the government for poor relief during the Great Depression. (News clips I'd read from 1936 about lynchings cited several instances where Communism stood in as a proxy for race, as if hanging a black Communist killed off two infections for the price of one.) I had read where about 100 African Americans had gone to Spain, and reading this immediately sparked a "why?" Why would these dispossessed men and women fight to protect freedoms in Spain that they couldn't enjoy at home? This type of choosing against the grain always hooks the writer in me.

Here is the 62-word kernel of the script:

After local whites lynch his wife as a suspected Communist, African-American Jesse Colton flees his small Mississippi town and travels to Spain in 1937 to fight Franco. But there he finds that his real battle is with the fascists back home and that he must return to face them down if his life, and his wife's death, is to have any meaning.

Coming up with the return journey for Jesse turned Ain't Ethiopia into a dramatic script instead of just a historical narrative. Up to that point, I struggled with how to turn my admiration for the people who went to fight into a compelling dramatic story in short, how to transform the documentary and educational into something personal and morally troubling. It is one thing for Jesse, in his new-found freedom as a freedom fighter, to face the gigantically repugnant figures of Franco, Hitler, and Mussolini; it is another, more harrowing, thing to face his wife's killers and face them squarely. And that could only be done at the original crime scene.

The script had had a good reception at the IFP Market & Conference in September 2004, being one of 200 selected projects (from over 1600 submitted). The script reader, who had recommended it for inclusion in the conference, told me that he felt that at the end of two hours he had been taken on a journey he never expected to make and that he thought script very fine indeed honey for the ears. The IFP is not buy/sell kind of event, so even though I "pitched" it, I did it in the context of talking with fellow-hungry movie people, all of us looking for some crease in space-time that would allow us to leap forward past time and chance.

My next step (label it "naοve") I took, buoyed by these good responses, was to seek out directors/producers/actors of color who might be interested after reading my query to be interested enough to read the whole script. So I signed on for the free 14-day trial at IMDb that allowed some deeper spelunking on the site for contact information and extracted what I could. Then mail-merge, query letters out, waiting by the mailbox.

And bang against the next installment of Catch-22: we can't read your ideas because you may sue us if we ever come up with anything remotely similar, so we must, unfortunately, remain agnostic about the contents of your missive. Only the agent of Denzel Washington took pity on me. He made me sign a form that forever and a day held them all blameless, and then took receipt of my scripts and after a respectful interval (so that I didn't feel that they were immediately circular-filed but only gradually circular-filed) returned them to with his and Denzel's regrets. I pretended that Denzel had actually touched them, leafed through them, and shook his head at being unable to forward such a promising script and the promising writer who had birthed it. I kept the returns in very neat stacks until I couldn't bear their mock anymore and ditched them with the recycling (not before extracting the return envelope with the still-usable stamp there would be others, I said defiantly, who would make good use of these SASEs).

What was a poor flicks-scribbler to do? And then the siren call of the festivals. That was it! That was the ticket in!

The One I Won

I can't remember the most recent tally of film festivals/competitions in the United States for some reason, 3000 sticks in my head, but that's probably wrong. But there sure are "a lot" (however many that is). Not all of them take screenplays as well as films, but there is a subset hunk that do, and those had my bulls-eye painted on them. (Another constraining factor is, as always, money. Theatres may charge, at their most gouging, $25 for an entry fee I've never seen one over that. But film competitions are usually double that for the early bird more expensive later for the late bird. Limited means, limited choices.)

I submitted, of course, to Sundance and the Nicholls Fellowship (very complimentary rejections from both), Scriptopalooza (less soothing rejection notice), and Filmmakers.com

And lo. And behold. An email from Filmmakers.com: "The Top 400 Scripts" (subtitled "From the 1273 Scripts Submitted"). And lo. And behold. Ain't Ethiopia is listed. Right up near the top (thanks to alphabetical order). Hmmm....

A due date is posted for the next round: the top 200. Date comes: there it is again. The top 100: there it is yet again it has dodged the bullets well, look quite spry and natty. The top 50. The top 20 (from which the winning 10 will be chosen). And then and then third place. Third place. It won something. I won something. I'm going to Los Angeles, to the Screenwriters Expo 4, to pitch the piece and sit in the same room with William Goldman (well, within proximity of him) and suddenly be plunged into the world that a year ago had not been open for me to plunge into.

And the whole damn thing torqued me around. It wasn't joy or possibility that flooded in but the noun form of being unnerved, unmanned. I didn't want to go, compiled "reasons" why I couldn't (didn't want to lose time from work, couldn't afford the costs) but the barricade of excuses pointed to something else, which I am now only beginning to unpack as I pack up for my west-flight: something to do with age, entitlement, and fear.

What's This?

Age

"At my age I shouldn't have to" suddenly this phrase is popping into my head. Now, I'm 52 years old not spry but not sclerotic. (The Marvelous Maria will attest that I have not lost my nerve endings.) But "at my age I shouldn't have to" begins to sound, well, positively geezerish.

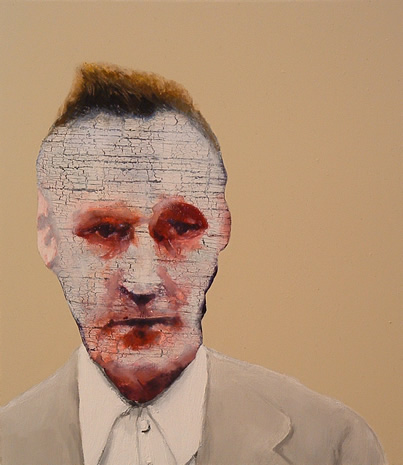

|

Geezer by Ian Healy

|

|

But I had to admit that something about feeling "aged" fed into the intital feeling of reluctance when I got wind of the award. Movie-making is a younger person's game at least that had been the scuttlebutt in my classes, through the articles I'd read. Many of my screenwriting teachers in the Dramatic Writing program at NYU were older gents who seemed tired out by the scrabbling for work and the quickness with which they could be discarded, no matter how pedigreed their rιsumιs. I suppose I had soaked up enough of that jadedness so that the prospect of a ride on the movie carousel just pre-wearied me. I didn't want to muster, didn't want to gather, didn't want to exert I would much prefer it if someone would just hand me the prize to which my age recommended me and spare me this unseemly sweating and anxiety.

With mild alarm I realized that I had slipped into....

Entitlement

Rather than being jazzed by the chance to go pitch a screenplay that I'd worked hard on and felt affection for, the California call, provoking the tiredness mentioned above, felt like a sentence to hard labor,

|

The Visitation by James Christensen

|

|

yet one more slog toward a success that with each year feels less and less possible. "I have put my time into the universe," I groused, "and it's about time the universe paid me back." Even as I said it I could hear the absurdity of it there is no connect, there never has been a connect, between virtue and reward, between effort and profit. As The Preacher says, "luck and chance happeneth to them all."

But part of me hungered for "the visitation" that event of luck when someone decides to champion the work and suddenly one is not alone in cutting through the static to be heard. And it is luck the artistic director who happens to have the right cup of coffee in hand as he or she turns back the cover and begins to read, the spouse of a celebrity sitting in the audience who takes a shine to whatever is presented, the unexpected call saying you have won a MacArthur, and so on. We've all read about events like these, and each of us, I would guess, secretly hopes for a patron, or something patron-ish, to come along.

And the wish-ache that comes with such waiting also made me realize that I had to admit that I felt....

Fear

The fear I felt was not gut-emptying terror or the paralysis of overwhelm but the more pedestrian fear of looking and feeling the fool when I go to pitch my ideas. Okay, so I can write well, I can wield the word with slice or softness but, damn, to get up there in front of strangers and, well well justify myself is just too much, too much indeed (sound effect: splutter, splutter in soft rage). The surface self-justifications for the fear are that the work should speak for itself, art should not bow to commerce, etcetera, etcetera.

But the sub-surface is more real: What if I suck at pitching? What I can't make the grade? What if everything I've tried to create melts into silence because I can't bring myself to speak brilliantly and sharply about what I love? The look-down-the-nose at the messiness of the marketplace is just a mask for cowardice. My high-toned reluctance was really a yellow-bellied kvetching.

|

From perth.indymedia.org

|

|

This effort at selling does not come naturally to one who dubs himself a writer. Canards and stereotypes aside, writers do crave silence and solitude, the lone creative effort, worlds spun from nothing more substantial than synapses. They are in the world but not necessarily of it, and even that "in" can be a tendril-thin tether. To leap into the mud-wrestle of a pitch session is to be wrenched into full solidity, and the border-crossing from virtual to actual can callous-up the nerve-endings something fierce.

But writers good writers are experience-harvesters, and that's the attitude I've decided to take: to reap what I can with brio and a wry smile, train myself to be the best damn pitcher I can be, making sure it comes out of love and humor, and let's see which angels come to visit.

THEPITCH: PART1 THEPITCH: PART1

I have to admit that I had always heard about "pitching," and it was easy to enough to see it parodied on comedy shows like Saturday Night Live and movies like The Player seen it enough to conclude that any breathing carbon-based life form that had an inkling of sentience and self-worth would never

|

Ready to smoke one in!

|

|

make it part of their life's work to go begging like that, to fillet life's plenty into such genre'd and salable strips of jerky. Art could not, should not be, boiled down to the duration of an elevator ride (to use one measure of a pitch's perfect length) thus saith the aesthete.

But I had three of them as part of my winning package three little eggs ready to be omleted as part of the tribute given to a winning writer. One cannot hold on to unbroken eggs forever they will be opened, one way or another, so the questions become "how" and "with what grace." Hmmm.

And what was even stranger, at least to a playwright, was the concept that a writer could "buy" more pitches at the conference, for $25 a toss. It sounded like the discounted Catholic practice of buying indulgences, or the secular version of that, "pay to play." One carries the pitch around the way the old-style door-to-door salesmen used to heft their sample cases, throwing them out open for anyone to see, not a bit of reluctance to show off and tout the wares. A playwright would never do that. Or, more accurately, a playwright would never have the chance to do that kind of bidding and selling at a "pitchfest."

|

Got it!

|

|

In the movie-world, it seems, if art is the Temple, then the producers are the money changers, and the two muck along just fine. In the theatre, however, the money-changers are elsewhere the Temple is decentralized and the buying/selling takes place behind a veneer of gentility and "development" and inside some kind of black-box that is opaque to all the supplicants hoping for a slot in a season or even a script-in-hand barebones reading. At least at the pitchfest one can belly up to a table, look another human being in the eye, and say, "Here's what I got what d'ya think?" Who could ever have a chance to do this with an artistic director of a theatre if one is not already one of the select, much less walk around a large conference room and, like speed-dating, hang out what you own, and if it doesn't get a bite, go on to the next set of teeth?

I've talked about this before, in an earlier essay titled Market, when I attended the IFP Market & Conference in September 2004. As I said there, "Given all this brazen commerce, why would I, self-proclaimed theatrophile and hater of commodification, be pleased to be so embedded with the money-changers? In part because they were so honest; in part because there are actual chances to make a living through my dramatic writing (slim, to be sure, but gargantuan when compared to the non-existence of such chances in the theatre world). And in part, and I feel surprised saying this, for the entrepreneurial spirit I sensed everywhere and in everyone. Here were people unabashed about selling themselves (and it is always the self that is sold the product, the project, is just a calling card, a preliminary knock on the door). Here were people unafraid to push hard for what they believed in not a noble 'believed in' because larded with all levels of self-interest and competitiveness but still a 'believed in' that got them up in the morning and forced them to move against gravity and ennui and defeat."

But then, there was actually writing the pitches I wanted to deliver that proved harder than I thought.

THEPITCH: PART2 THEPITCH: PART2

Okay, so the image below is a little exaggerated but only a little. The common perception of "the pitch", at least among theaterphiles, is that it takes the heart out of the art

by reducing the complexity of the narrative to an easily and quickly digested form. But I would argue, having struggled for hours one evening to extract three "pitchable" pronouncements from my already-written screenplays (Ain't Ethiopia and two back-ups, By The River and The Sunlight Dialogues), that shaping a pitch, rather than pithing the heart out of a narrative, sharpens it. Or, more accurately, the time-, word-count-, and presentation-constraints of a pitch forced me to solidly map out the cardial nerves that made the story pump its narrative blood.

In fact, I would go so far as to say that crafting the pitch actually made me fully understand the story I had written. I mean that, as odd as it sounds. For instance, I "sort of" knew the flow of Ain't Ethiopia, knew the act structure and the turning points, and so on. But the press of having to make all of that clear in under two minutes to a stranger who, like David Spade for Capital One, is primed to tell me "no" and move on, forced me to publish, in plain sight, the "architectural drawings" for the work's structure: this leads to this, and that then curls back to here, which then sets up this, where I bring back in this point that I had set up back at the beginning, and so on and so on, and in the end, this is the "take-away" for the audience (to use David Mamet's term), this is what they will port away with them as an understanding about the movie, what they will tell their friends when their friends say, "So, what movie did you see this weekend?"

So, rather than take the "heart out of the art," the pitch, like an X-ray, brings the bones to light, makes clear the structure (with all its struts, hinges, and pivots). The pitch, then, is part of the storyteller's art, not its antithesis or destroyer, the way an epigraph can thematically prepare an essay or (in a drier image) an abstract can distill a dissertation. And I would further argue that most of that plays I read as a reader for theatres suffer from not having gone through the pitch-process, where the writers would be forced to come up with a description of their work whose sole purpose is to convince a reader to want to read it. And I would go further than this "further" and say that many writers, if they did this, would find out that they have scripts that don't do anything dramatically, that they are static and "character-based" (i.e., static) and go narratively nowhere because the scripts have no forward momentum. If theatrical writing can learn anything from the movies, it is this: economy in words, thinking in visuals, and a narrative structure that constantly triggers new choices and never lingers unless it's necessary to the story-telling.

Next up: the Expo!

The Rest

The air palpates with tension.

The way it works: everyone has a designated pitch time (done in five-minute increments). To get a feel for what it feels like to pitch one's golden moment in such a short time, try explaining anything, no matter how simple or mundane, to a perfect stranger in five minutes while simultaneously being spirited but not desperate, committed but not obsessive, confident but not arrogant, excited but not nervous, sincere but not sappy, economical but not terse tongue-tied and dry-mouthed will be the least of your problems. Did I also mention that the future direction of your life may depend upon the outcome of your spiel? I didn't? Oh, well add that in, too.

|

Up against the wall!

|

|

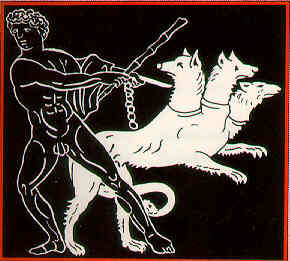

The moderator/gatekeeper/three-headed Cerberus comes out and bellows "All the 10:15s in a line against this wall," and the 10:15s, obedient and puppy-eager, cleave themselves to the wall. Some chat, but most are running their pitches through their brains and mouths. An alien observer, not knowing the context for the gathering, would conclude that something is physically wrong with these creatures, afflicted as they are with tics, whisperings, lip-movements, hand-jerks, darting eyes. Not to worry it's just rehearsal. It's normal in this abnormal place.

Then the moderator/gatekeeper/three-headed Cerberus announces that the 10:15 meeting is now in session and begins punching tickets as the supplicants file past him. Inside the entryway to the pitching hall, the 10:15ers bunch up again in front of a one-headed moderator/gatekeeper, who with practiced sarcasm reads them the rules: no business cards left behind unless asked for, no lingering after the "all-clear" bell is rung, no falling to the floor in apoplexy if a producer does not ask for a copy of your script, and so on. They all nod without smiling all humor has abandoned them, so tight with expectation are they. Laughter? Hah no time for laughter! We're here on serious business!

|

And they're off!

|

|

Then out they go again to fit themselves into the cattle chute that will, when the doors are opened, spill them into the pitching hall, where they will spread across the room exactly like the pioneers in the Oklahoma land rush. Meanwhile, fidget time a little chat and chatter, more rehearsing (mumble-mumble-mumble, gesture, grimace), milling about they are cattle waiting for the slaughterhouse, the only difference being that they have chosen to stick their necks out and have them jugulared. No one forces their heads onto the chopping block they put them there themselves.

And then and then and then the door opens. Land rush time! People sprint to the their designated tables, ready like a rocket reaching zero to launch into their pitch.

|

Please oh please oh please...

|

|

And the five minutes are off!! Pitch pitch pitch pitch pitch the whole universe is, for five minutes, all pitch, and (to use a sports metaphor why not? it's a homonym) there are curveballs and knuckleballs and sliders and streamers and overhand and underhand and every possible manifestation of vocal physics to get that idea across the 18" of white-clothed table into the strike zone of the producer's ear, waiting to hear that "Steee-rike!!!! Send me a script! Send me everything you have!" Or not. More likely not. A ball "Send me a synopsis." High and outside "What else do you have?" In the dirt "Thanks, it was nice talking with you." "Thanks, it was nice talking with you"? oh, man, did it really suck that bad?

But no time for critique "you have thirty seconds left" gather papers, notes, pride, guts on the floor, stuff back into the bag and belly, get out, next crew in, get out, get out, get out and get in line for the next pitch. Fall off the horse, get back on. Fall off the mountain, climb back up. "Yeah, so it didn't work for her it'll work with someone else. Yeah, yeah it will, it will, I just know it will."

And you can always buy more pitches at $25 a pop. Next?

My first pitch went well pretty well. I lucked into someone who actually found the idea of African Americans fighting in the Spanish Civil War an interesting thing to learn about, and so I was able to converse with her about the story rather than run my flag up the pole to see how it waved that is, a moment of human, as opposed to contractual, contact. I had gotten a helpful clue from a pitch-practice session the day before with Gary Freeman, who thought it would be good to note the strikes against the idea in terms of its marketability. (Note: a "marketable" script and a "good" script are not cognate marketable scripts can be horrible from an aesthetic or artistic point of view but have the possibility of making money for its makers. Thus a good script is one that will get made that is the only litmus test for "goodness.") It was historical, it was a drama, and it took place, in part, in a foreign land: foreground these so that the producer knows that you have thought about the obstacles and have found a way to make these apparent minuses into pluses for the pitch, which I was able to do.

So she wants to see a synopsis of the piece not as good as a read but not bad given the lack of marketability of the script.

My second pitch took an unexpected turn, which taught me something about preparation and presentation.

I spoke my spiel, and they found it interesting but not useful to them. "What else do you have?" Now, I had prepared, in my head, a pitch for By the River but had not practiced it. (The screenplay is based on my friend's memoir A Question of Color). As their words registered, I could actually feel like a tangible physical torque my brainware shift gears booting up a new program, the neuronal hard disk whipping through its file access table to get the right data, the words popping up on the screen, the text-to-speech software kicking in all in the space of an "Um, well, I have this ". And out came the story in a much less prepared and because of that, a much less stilted manner. They liked it. They asked me if I had ever seen it as a TV movie, on a schannel like HBO, and I shot back immediately, with sincerity (with completely sincere sincerity completely sincere did you get that I was truly sincere?), that I'd always thought that that would be best way to present the story. That clinched it they want to see the full script. "You have 30 seconds to go! " the voice of the pitch-god blares out just enough time for him to jot down his email address and for me to gather papers and self and shake hands and say "Thank you" and vacate in time for the next hungry artist.

In thinking this second pitch over later that day, I realized several things.

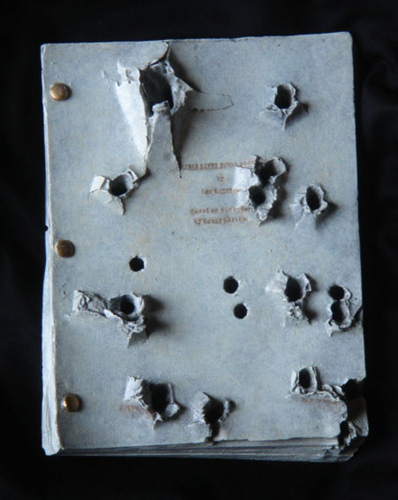

|

Screenwriter Tom Benedek became so frustrated, he drilled his scripts with bullets - then bronzed them for display. (See

www.tombenedek.com)

|

|

First, the eagerness with which I told that them an HBO production of the script would be the perfect medium for the story didn't feel false the end-point, after all, of all this sweaty effort is to get someone interested enough so that they won't say no, since they all have more reasons to say "no" than "yes" to all the ideas coming down the pike. It also told me that, at least at this point in my "career," something like "artistic integrity" is mostly irrelevant because screenwriting is not really a medium for self-expression, like novels or poetry or even plays. Screenplays are commodities, they are "properties." They are meant to make people money, first and foremost, and if along the way an artistic thing happens, all the better. This doesn't mean that a screenplay is only about money. For the writer there still has to be an emotional and artistic connection to the material otherwise, it's just hack work, no different than a butcher hacking out sirloins and rib roasts. And the audience still wants a story that will move them, perhaps even educate them (a little not too much), at the very least make them feel that their money and their two hours haven't been wasted. But these elements are important only insofar as they end up creating a product that will, after all the money has been invested, returns all that money many times over (the more times, the better, especially in the overseas markets).

For me, then, if I am going to write screenplays, I need to embrace this monetary fact and shift myself accordingly. I need to come up with ideas that production companies will want to buy and people will want to go see and which will satisfy me as a writer (note the sequence of those considerations). It means that I have to "contemporize" myself, become more aware of what is flowing through the zeitgeist than I am now (meaning not only through the culture but also through the trade publications the movie zeitgeist is a parallel universe that mimics, but is not the same as, the culture zeitgeist). I have to re-set my brain about how story gets told by seeing and hearing things in log-lines (as was said time and time again, Hollywood lives on log-lines). It means marketing myself as a commodity (as one instructor put it, "You are the president of a business called [insert name here], and you own 100% of the product "). It means getting representation, manager or agent (still can't figure out the difference between the two but both will take money from you for their services). It means, in short, re-equipping my life as a dramatic writer, configuring it into a business, the "business" part of it the means by which one gets the "end" that all this effort is being spent to reach: recognition, some satisfying level of monetary success, some happiness in doing well what one can do well.

How does all that feel? Let's say this: sitting on the cusp sounds painful, and it is.

This is not the world of theatre.

The Final Day

I had two pitches on Sunday. The first didn't really care for either of the ideas, though he did like By The River better. But he was a young guy (wore the baseball cap), and I'm not sure I would have had anything for him anyway and he did have a point about the hero being killed off in the end not the usual Hollywood formula for the hero). He said that that was not necessarily a drawback. He complimented me on the pitch even if he thought it was not going to be an idea he'd move on.

(Before going in, chatting in the line,

|

Zombie love is sooo good!

|

|

I spoke with Nick, a young gothish-looking man, about his screenplay Blood and Roses, a zombie love story. Later, when I caught up with him, he had practically sold it to a number of companies and was ready to quit for the day. As said above, the best way in is a low-budget horror movie. He is in.)

The second pitch went better and "better" in ways that were quite instructive. First, his name was Michael (Ades), so I had an immediate chance to make a quip about "Michael" being a great name. He was dressed casually but not sloppily: nicely cut white collarless shirt, black pants. Open face (no goatee) and short black hair brushed back, swarthy skin perhaps Italian or Greek. So the pitch started off on a natural note. And I began the pitch session differently than I had before, as an experiment, because of how By the River had now come into play from the day before.

As I sat down, I told him that I had two ideas for him (fully expecting him to say something like "Well, let's hear your first one" and would go into the by-now standard spiel for Ain't Ethiopia. But instead he stopped me and said, "Which one is most marketable?" I was not ready for that which actually proved a good thing. I hesitated (dramatically, I must say) and said (with a practiced look of slight indecision), "Probably my second one it's a love story." And he replied, "That's the one I want to hear." So I pitched him By the River, and it had several things going for it (a good lesson, this one): it was based on a published book, I had the rights to adapt the book, the story was a relevant story even though historical (we had a good conversation about how the multi-racial identity issues in the story still resonate today), and, above all, it was a love story. Love story. Hear that? Love story. We left it with his taking my email address and a promise to check out the book if he thought it was good material, he would ask to see the script. Not as good as a "Send me" but better than a "Thanks for taking the time..." (translate: no, no, no, no, no!)

What I liked about the second pitch was that it felt very natural (or as natural as pitching can ever feel), and it also told me that you have to go in with a really solid product, fully thought out, fully "scripted" (though more improvisational than memorized a riff rather than an audition piece). And one other thing, said by the pitch-wrangler, made the pitching more sensible: "Consider it like a job interview they're buying you, not the script." And I always do well in job interviews.

So, did pretty well on all four, especially for a "rookie pitcher."

The rest of the day moved smoothly along. The lecture with William Goldman was delightful (he walked into the room and several hundred people stood to applaud him like a rock star). He was charming, caustic, grandfatherly. (Some jerk actually tried to hand him his screenplay on the way out!) I took a workshop on writing subtext (skillfully done by Karl Iglesias, mostly as a promotion for his book and DVDs). Then the closing ceremonies, with awards given and so on. (The awards for the screenplay contest many thousands of dollars handed out did not include one straight drama but instead awarded people in the genres of thriller, fantasy, horror, comedy, romantic comedy. Drama is a forgotten category something Goldman talked about in his remarks. The studio execs, focused on the "first weekend" and scared about risking anything, including their own jobs and not necessarily being film-lovers or "filmists" themselves they have made themselves believe that dramas will not make money that is, the kind of money they need to justify and maintain their jobs.)

And now home to mail out my thank-yous, send out what was requested, sift through the paperwork, and figure out what would make me "marketable" as a writer and still enjoy the process and still be able to live in New York and not move to LA. "Marketable" it's an interesting term because anything can be marketed, as was shown by the ideas being pitched at the Expo it doesn't have to be good in the usual artsy sense of "good" to be good "good" means "sellable," and I think I can do that, at least once or twice, and that's all it takes, that's all I want.

The adventure continues.

|