|

“Body in a Dream of Spring” —Lynne Knight

Overnight the snow’s blown back

along the fence, baring the field’s dull

grasses, so when the villagers walk

the rutted path toward church, they dream

of spring. Most wear crow-black coats

or dresses, but there’s one coming

the other way headed out øf town

in a green coat, hands deep

in his pockets though he’s free

of all constraint. The villagers greet him

in secret envy of his green coat ways,

then look quickly away as they hurry on

to the sermon, cold traveling up their legs

in defiance of gravity, like unhappiness

that keeps rising. Oh, why can’t they

set it down, why must it get out of bed

with them, slip into their clothes, wait

in their mouths like Amen. And why

should that green-coated one go free.

They’ll resent him less, come summer—

but snow and cold will make them haul

their dark coats from the attic. Then,

with winter eyes, they’ll see him again,

strolling in the opposite direction.

All of them will long to turn and follow.

Next year, they’ll promise, holding

their black coats closer, hurrying on.

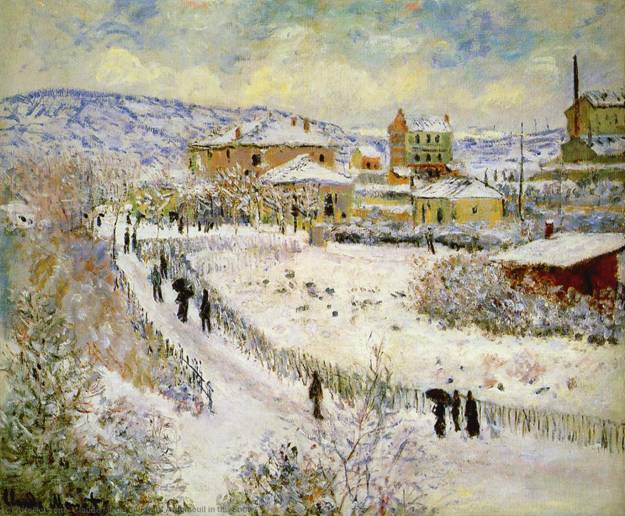

Lynne Knight’s “Body in a Dream of Spring” was inspired by Claude Monet’s

“View of Argenteuil,” which she saw, along with other snow paintings, at the

DeYoung museum’s “Impressionists in Winter” exhibit in San Francisco in

1999. Monet’s painting is one of fifteen of the exhibit’s paintings by Monet,

Pissarro, Renoir, Sisley, Caillebotte that inspired the poems in her book Snow Effects (Small Poetry Press, 2000 and 2008).

Poems that focus attention on a visual work of art are called “Ekphrastic”

(from the Greek word “ekphrazein,” which means to describe or proclaim).

Famous ekphrastic poems include Keats’ “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” Rilke’s

“Archaic Torso of Apollo,” and Auden’s “Musee de Beaux Arts.” Those poems

not only vividly describe the urn, the fragmented statuary of Apollo, and the

Brueghel painting “The Fall of Icarus,” they lead to convincing universal

insights inspired by the impressions the art makes on the poets.

Like her predecessors, Knight translates visual into verbal art—color, light,

and texture into story, symbol, and sound:

“As I looked at the paintings” [in the exhibit] she notes, “it seemed to me

that they were more than studies of light. They were variations on a

universal theme: the passing of light into dark, of love into death. I saw

them as meditations on the body in winter, and they led me to my own

version of snow effects.”

Claude Monet, View of Argenteuil, c. 1874, oil on canvas

Knight sees something unusual and easily missed in “View of Argenteuil”

that leads her to translate Monet’s visual work into a convincing narrative

with universal meaning that rings especially true for me, partly because of an

experience I had, with my wife and children, years ago at the Steinhart

Aquarium in San Francisco.

As we approached the circular tank, hundreds of fish were swimming

around in the same direction. Suddenly a fish came into view swimming the

other way. Even our five-year old daughter found this behavior intriguing.

We stood in the same place, transfixed for a while, as the herd of conformists

streamed by; waiting for our rebel to re-appear, and it did so again and

again. Did this fish have a reason for choosing to swim the other way? Did it

know something its brethren didn’t?

Knight’s poem begins with her noticing that although a dozen of the villagers

in Monet’s painting are headed towards the church in the upper right corner,

one is going the other way, passing them by, “headed out of town,” “free of

all constraint.” While the funereal “crow black” coats and umbrellas of his

fellow villagers suggest winter, discomfort, and death, his green coat, his

hands thrust “deep in his pockets” suggest the jauntiness of spring and a

celebration of life.

Once the contrast between Monet’s green and black coated figures is

established, all the elements of his painting fall into place. The communal

“body” of the parishioners, united in their habitual movement towards

church and a sermon that will probably diminish the value of earthly

pleasure is challenged by the joie de vivre of the “green-coated” one’s

individualistic “body.”

For although Monet is outside in the snow, Knight takes us inside the

psyches of his villagers. As they trudge along, bundled up in dark clothing,

they keenly feel “the cold traveling up their legs in the defiance of gravity.”

They too are looking at Monet’s painting and observing the tinges of green in

the grass and foliage that last night’s wind and snow have exposed. Still

sleepy after too early risings, they cannot help but dream of spring.

If we could press a button and animate Monet’s painting, frame by frame, we

would come to the poem’s serial epiphanic moment; for each of the villagers

must briefly become an individual who must pass by and acknowledge the

existence of one who, unintimidated by winter, personifies the spiritual

optimism and buoyancy of spring.

For a fleeting moment each villager feels that it may be possible to break free

of winter—spiritually, if not physically; but, slipping back into the communal

“body,” each will “look quickly away” and “hurry on / to the sermon,”

secretly envying the green-coated one, asking why unhappiness must “get

out of bed with them,” / slip into their clothes, wait / in their mouths like Amen.”

The green coated one’s recurrence towards the end of the poem suggests

that he is more an apparition, more an impulse in the collective psyche,

more symbolic than literal. As the villagers “haul / their dark coats from the

attic”:

with winter eyes, they’ll see him again,

strolling in the opposite direction

He exacerbates the dissatisfactions we all feel at being restricted by our

behavioral patterns, our roads too mechanically taken.

“Habit,” Vladimir observes in Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, “is a great

deadener.” Marcel Proust saw that, although that’s true, habit also liberates.

As my literary pal, AI, puts it:

“Proust describes the liberating effects of habit by illustrating how it can

provide a sense of comfort, stability, and familiarity in our lives. Through

routine and repetition, habit can offer a sense of security and ease,

allowing individuals to navigate their daily lives with greater efficiency

and confidence. Additionally,Proust suggests that habit can facilitate the

process of adaptation, enabling individuals to adjust to new

circumstances and challenges more readily. In this way, habit can serve

as a form of psychological refuge, providing a sense of continuity and

control amidst the complexities of existence.”

Simply put, human beings have a love / hate relationship with Habit which

leads to the mental tug-of-war that Knight so powerfully explores via

Monet’s painting. As in a dream, the villagers proceed through time’s

seasonal cycle, from light to darkness, winter to spring and back again, trying

to deny how the cycle must end.

The final lines of “Body in a Dream of Spring” poignantly express Knight’s

sympathy for those who long to break free from habit but are too invested in

the comforts and illusions it offers to attempt to change their lives.

We are left shivering with the poet’s villagers as they pass that irrepressible

creature once again who continues to silently suggest that alternative

directions are possible:

All of them will long to turn and follow.

Next year, they’ll promise, holding

their black coats closer, hurrying on.

|