|

As many readers of my pieces know, I have great admiration for the British playwright Howard Barker; his work has prompted several essays for Scene4. For all of that, though, I have never seen a production of Barker's work. But June and July 2007 in New York offered something of a Barker mini-festival with two works scheduled for performance: "Scenes From An Execution" (ending its run on June 10) and "No End Of Blame" (ending its run on July 14).

So, off I go to see "Scenes From An Execution" first - and, oh, what a disjunction between the theatre in my head as I read Barker's play and what moved before me on the stage.

"Scenes From An Execution" uses a well-worn trope as its starting point: the conflict between the artist and the state (or, better said, between the artist as truth-teller and the state as truth-bender). Venice, fresh from its victory at Lepanto in 1517, which secured itself against the Ottoman Empire, commissions a painting of the victory and hires Galactia, the best painter in Venice, to execute it. (Barker invented Galactia, but she bears a close resemblance to Artemisia Gentileschi, born in 1593 and renowned for being both a painter and a woman painter.)

Galactia wants her painting to tell a truth about the butchery of battle, and the Doge of Venice (and his brother, the conquering admiral) want the painting to celebrate the glory of the victory and the city that financed it and brought it off. Therein lies the contest of wills: between differing notions of authority, of power, of art's purpose. The play ends with a twist in our usual romantic expectations about artistic integrity, and the twist means to (as the whole play has meant to) make us think more deeply about power—about its seductions and perks and paradoxes and beauties and nourishments.

The production disappointed me because I felt it was not hard-nosed enough about Barker's hard-nosed examination. If Barker's plays have a temperature, that temperature would be cool in order to work against what Barker sees as the warmish and moist sentimentality of contemporary playwriting, with its emoting and sense-memories and psychologized characters. In this production director Zander Teller seems to have directed Galactia (Elena McGhee) to mine the character's internal strife over battling the Doge and the state to achieve her truth-telling in pigments—thus, much sighing and purse-faced angst: the romantic meme of just another poor artist (the "good guy") caught in the nasty nets of state control (the "bad guy").

But Teller should have gone in the opposite direction, which I believe Barker laid down in the script: an artist every bit as calculating and selfish as the State and the Church she fights, someone we may not want to hug but nevertheless will respect because of the force of her inhumanness. Yes, I did say "inhumanness." For Barker, such a noun is not a drawback but is, as my wife would say when she sees something overly saccharine, "a bite of the chili pepper": the thing that clears the palate of the sentimentalized Christian ethos that dominates the current narrative practice of bringing light and understanding and forgiveness (if not redemption) to an audience, an ethos that Barker has scorned time and again.

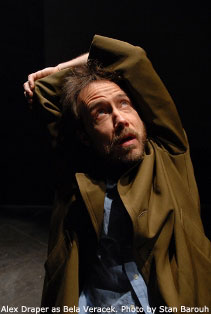

"No End Of Blame," the production that signals the return of Potomac Theatre Project to New York City's theater scene (after a 20-year sojourn in Washington D.C.), fared better in this regard. Bela Veracek, a Hungarian cartoonist who survives World War I, the Russian Revolution, World War II, and the Cold War thereafter, is in constant battle with the commercial and governmental institutions  that praise and want to use his truth-telling talent but in ways that forward their own agendas, not his. (Again, Barker uses the cultural contest of the artist versus the corporate entity.) Director Richard Romagnoli kept stage and lighting design simple and spare, using common objects and defined lighting to set place and time. Rear projections of the cartoons of Bela were integrated neatly into the flow of the play's action. that praise and want to use his truth-telling talent but in ways that forward their own agendas, not his. (Again, Barker uses the cultural contest of the artist versus the corporate entity.) Director Richard Romagnoli kept stage and lighting design simple and spare, using common objects and defined lighting to set place and time. Rear projections of the cartoons of Bela were integrated neatly into the flow of the play's action.

Yet, to me at least, because the production lacked a certain fierceness—or, to re-use the term, "inhumanness"—Bela comes off as a victim of bloody-minded and art-indifferent institutions, his artist's soul sullied by the demand that his work have purpose and utility. To be sure, that element is in there. But it ignores that Barker built in to Bela's character his, Bela's, own bloody-mindedness and indifference that make him, in some degree, an anti-victim, anti-humanitarian, anti-redemptionist. Bela wants to be a scourge, not a savior, and as with most scourges, Bela is not necessarily a likeable person, but he is a person whom we can respect and admit that we need.

In this essay, I do not want to re-direct either Teller's or Romagnoli's direction (though, if they ever wanted to discuss it, I would enjoy the engagement). Instead, one thing that came to mind as I left the theatre each time is this: because of this ethos, this "regime of light," as Barker calls it, American actors and directors, in aiming to hit the audience member in the gut, miss what I call the "gut in the head." Let me explain.

This ethos comes grounded in a historical splitting of the human being into "head" and what I call the intestinal, such as the "heart" or the "gut" or the "liver" (as in medieval times). Two corollaries came out of this split. First, reason (the "head"), while glorious in its power to analyze, can never prove the truth of anything because, carried to an extreme, reason always undermines itself by coming up against this or that logical inconsistency. Authorizing the truth of something falls to the intestinal, the supposed locus of faith or intuition or sympathy. If one feels in one's gut that a thing is true, even if the head parades argument after argument against it, then that thing is true and must be followed. A tautology, of course (i.e., if I feel in my gut something is true, then it is true because I feel it in my gut), but nevertheless, there it sits, enthroned.

But what came to me after the performance was that this anatomy is too simple, which is why the productions felt less than full-voltaged. The head also has its own gut, and it differs from the one in the lower regions. This gut thrills to the truth of the intellect, to the cool aesthetic, to reason's scalpel, to the enstranged and the against-the-grain and the surprised expectation. To it, catharsis proves nothing, and being emotionally drained by Aristotelian fear and pity is simply a playwright's way of making the audience members powerless and passive voyeurs.

This is not a gut that most American theatre people know about because their training does not include knowing about it or cultivating it. But it has great power because it doesn't allow art to wash over us in order to pacify us; instead, it makes us work against the received cultural scripts that get in the way of understanding what is real and, by negating these scripts, makes us complicit in the act of making art. Barker captures this in his prologue to "The Bite Of The Night" about a woman coming to the theatre:

If that's art I think it is hard work

It was beyond me

So much beyond my actual life

But something troubled her

Something gnawed her peace

And she came back a second time,

Armoured with friends

Sit still, she said

And, again, she listened to everything....

And in the light again said

This is art, it is hard work

And one friend said, too hard for me

And the other said, if you will, I

will come again

Because I found it hard I felt

honoured

In reference to "Scenes From An Execution," the sentimentalized romantic approach to the issue of power in the play missed the gut in the head. If Teller had gone for that gut instead of the nether one, then the production might have tackled power in ways that would have made the audience more enmeshed in Galactia's struggle and thus more aware of their own ideas/temptations/desires about power. That might have made them more uncomfortable with the play or made the play too opaque—but, on the other hand, like Barker's theatre-goer, they might have felt honored rather than simply served or entertained.

If doing that, if going for the gut in the head, had made Barker's play come alive, I would have counted that an evening well spent. But in thinking about the gut in the head, it occurs to me that part of the reason why most Americans have such a turmoiled relationship with power is that they don't use the head enough (and the gut in the head) to think about how power is applied to them. Instead, they sentimentalize power, thrill to an intestinal sympathy with those in authority, intone phrases "like the power of the Presidency" to soothe their anxieties, and forget to listen to—or simply ignore—the gut in the head telling them to sharpen their machetes along with their skepticism. And if what they consume for cultural nourishment doesn't do anything to counter that sentimentality, or the tautology of the gut intuition, then there's no mystery to why we don't storm the White House and kill the Caliban in the Oval Office.

This is a stretch, but perhaps not much of one, and needs its own essay, in any case.

But the gut in the head—we certainly need more work that broadcasts to that. Barker is one. There are others. Let's find them and bring their dark light to the stage.

|