|

The Art of Deep-Sea Fishing

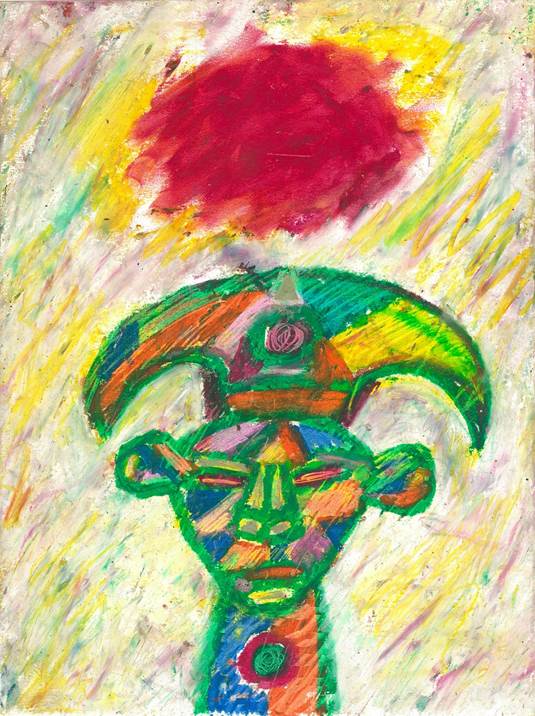

Brian George

Brian George, The Catalyst, 2004

1

C.J. Moore wrote,

"It was as if the poem came to life, and it was now reading itself from the great poem

of the cosmos. This was happening on so many levels that I was just a twig in a maelstrom. I danced with the experience, but it was like dancing with a shark. I

would find myself sitting in the university library, with my eyes buried in corridors of Egyptian temples that wound their sentences through languages that have long

since vanished in the sands of time, and I would suddenly wake up with a start and I would be reading Aurelia by Nerval, and I would see myself walking through the

streets of Paris, following Nerval's footsteps. I was seeing the hallucinations he saw, seeing where he was going in dark rooms when the vision stood before his

astonished gaze. Then I would suddenly wake hours later walking down the hill from the university, not knowing how I got there, and I would stop and feel the last light

filtering through the trees and wonder 'Who are you?'"

I responded: When I taught junior high art, I developed a strategy that I referred to

as "creative disorientation." Many students could not remember that, from the ages of three to seven, they were once in love with art, and most had come to believe they

did not have any talent. 'Show; don't tell," was the operative principle. It was not that I did not have any clear-cut goals in mind. A goal would be clear to me, but not to

them, and, by a process of "reverse engineering," I would lead students into an almost unbearable state of disorientation, which would swell into a kind of cognitive

crisis. I was familiar with this mini-version of the abyss. I had stared into it. It had spoken back. While the experience of disorientation would be particular to each, I

knew the general habits that were preventing these students from gaining access to their talents. Reactions would be supervised. Adjustments would be made. A nudge

here. A show of support there. At some point, almost inevitably, a student's cognitive crisis would flip over into a breakthrough, and it would open up a space in which

real learning could occur.

In situations such as the one that you describe, in which a hair's breadth separates a

breakthrough from a breakdown, I sometimes wonder if this is what is going on. With a goal that is clear to them, but not to us, perhaps our other-dimensional

teachers have reverse engineered a confrontation with the abyss. To this end, no academic knowledge would be adequate, and no human teacher could see far

enough ahead. Then too, such teachers know that ecstasy is our primal out-of-body state, and they do not lose any sleep if the student must be tortured. Some degree of

disorientation is a small enough price to pay to learn to what extent our vision has been compromised. We tend to see what we expect to see. We fail to grasp the

thread that would lead us through the labyrinth.

It is tempting to theorize that other methods could have been used, that a different

path would have led to the same end. Could our teachers not have given us a true and false questionnaire? "When I was a boy of fourteen," Mark Twain writes, "my

father was so ignorant I could hardly stand to have the old man around. But when I

got to be twenty-one, I was astonished at how much the old man had learned in

seven years." So too, it can be difficult for us to see that our teachers know much of anything, until, turning back, we note that the Earth has become a small speck in the

distance, and we then exclaim, "Aha!"

A straight line in not always the shortest distance between two points, and certainly

not in the education of a poet. If we had learned more about French Symbolism and Surrealism in school, it would have made it much more difficult for us to discover

these things for ourselves and would have removed much of the fun and mystery from the process. Lautreamont would have become an eccentric version of Longfellow. The quiz on Les Fleurs du Mal would have been as subversive as the one

on Hiawatha. Revolutionary fervor would have been graded on a curve, and school policy would have demanded that each essay should be taken back whole from a

dream. If, with a wink, a cuneiform chanteuse were to wave to us from a street corner—too hot, too avant-garde to be true!—school policy would encourage us to

make love to her in class. Upon climax, she would turn back into clay. Verese's Arcana would be the school's atonal fight-song, and Picasso's "I do not seek; I find"

the motto.

Hey, those ideas could work! A Man Ray photo could be used for the cover of the High Modernism textbook, perhaps the famous one of Meret Oppenheim standing

nude in front of a printing press, smeared in ink, with one hand lifted in an ambiguous gesture against her forehead. Our project would of course be subject to

approval by the Texas State Board of Education.

2

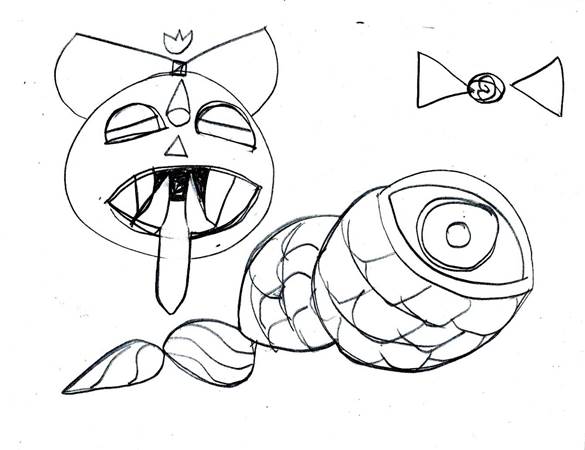

Brian George, The Reemergence of the Eye, 2001

In the Tao Te Ching, Chapter 73, we read, "Heaven's net is vast. It is loose. Yet

nothing slips through." And in Chapter 34, "The Way brings to completion but cannot be said to exist…It is always desireless, so we call it the small. The myriad

things return to it and it doesn't exact lordship, thus it can be called great." Once, there was only breathing. We did have bodies, yes, but each one was provisional, no

more than a convenience. Let us say there was a plan behind the original self/other disconnect, one that made sense to our teachers but none at all to us, in what form

could we glimpse this plan aside from that of a waking dream? We can ask, and insight may be given. We can summon back some portion of what we knew in the

womb, before the sky contracted, before the zodiac broke. The dream of everyday life may offer one more means of access. Events do not have to be strange to prompt

a sense of wonder, especially when we review these from a distance. When young, the world is outside, and the future is ahead of us. We might later wake while

walking up a hill, a hill we had not climbed in 40 years, and holding our hands up to examine think, "Who are you?"

The city in which I came of age was a self-emergent form—not reducible to the play

of social forces, far more than the sum of its parts—sometimes quietly and sometimes noisily alive, through whose streets I freely roamed. If its boundaries

were not fixed, if many small towns ringed the city, if it was only one metaphor in an infinitely long sentence, which was only one wave in an infinitely wide sea, the city

nonetheless served as a vessel for my growth. Its life may not have defined the extent of what I was; still, without it, I would not be who I am. I would not have had the

experiences that gave birth to my perspective.

I grew up in a factory area in Worcester, Massachusetts, up the hill from a freight

-yard, across the street from a field of mysterious weeds, and a few miles off from the pasture where Robert H. Goddard, the father of aerospace, used to scare the

cows with his rockets. At times, the ironworkers would roll up the doors to the foundries, and on our bikes, my friends and I would watch the red glow spill from

the furnaces, as ladles portioned out the white-hot metal from the vats. There were always scraps to take home, which we saw as treasures. In the distance you could see

the giant smokestacks. These came equipped with ladders, up and down which you could see the ant-like workers climb. I have never ceased to regard myself as a

member of the working class, or to love the area in which I came of age. My heart aches to remember the late-afternoon light of the "American Dream," which fades to

darkness even as I write. Some part of me is rooted in that neighborhood.

The stage-set in which I acted out my childhood—from, say, 1957-1970—should

perhaps not be imagined in terms of Worcester as a whole, for the city included a few affluent sections, which might as well have been on Mars. We knew that such

suburb-like neighborhoods existed. Few were jealous. They just did not seem real. No, my city was the eight miles or so that were visible from the porch of my three

-decker, which sat on a hill. Born at Fort Devens, at the end of the Korean War, I saw Sagittarius conspire with Celtic DNA to stamp me as a Roosevelt Democrat. I was

formed by the hands of that one moment on the clock, in the image of that way of life. It is possible, however, that other members of the working class would view my

interests with suspicion, if they had any idea of what those interests were. Who knows? I make sounds in acknowledgement when my neighbors talk about baseball.

I do not quote any poems by Rimbaud. I learned, long ago, to hide the greater part of my being, to think strategically and to operate by stealth.

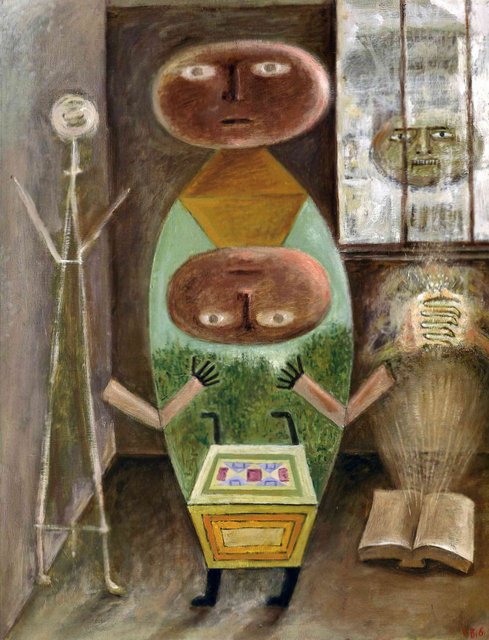

Victor Brauner, C'est La Vie, 1948

In Chapter 20 of the Tao Te Ching, we read,

"I am scattered, never having been in a comfortable center. All of the people enjoy

themselves, as if they were at the festival of the great sacrifice, or climbing the Spring Platform. I alone remain, not yet having shown myself. Like an infant who

has not yet laughed. Weary, like one despairing of no home to return to…While average people are clear and bright, I alone am obscure."

The world is vast and often hostile to our interests, those interests that might disturb

even our closest neighbors, if they did not live in a culture so dissimilar to our own. What has happened to the playgrounds of our childhood? Most are probably much

less violent than before, but we do not stop to spend ten minutes on the swings. Twenty-six oligarchs hold as much wealth as one-half of the world's population. The

poet has no more importance than his shadow. Ok, then. This is where his heartless teachers left him, with no grades, good or bad, with no avant-garde manifestoes to

distribute. They did not even leave any notes when they drove their cars into trees, when they leapt off of their roofs.

There is a painting by Max Ernst called Revolution by Night. This title has always

sent a shiver down my spine. When else should a true revolution happen? It must well up from the Apsu, from the waters of the Abyss, from the secret spaces of the

void beneath the Underworld, to only gradually emerge into the light of the public square. The stars can then, from an inconceivable distance, also lend a hand. Diana

Reed Slattery, in her essay "Shifting to a Psychedelic World Culture," writes, "Without 'silence, exile, and cunning,' and the secret Dublin of the soul, I would not

have accomplished my own research, that noetic quest to understand an alien language, Glide." To be alienated may be less of a punishment than a

strategy—imposed, by circuitous fiat, from beyond—which the poet may be the last to understand. The poet/revolutionary is a latecomer to the scheme. He must figure

out where to place the incendiary device—for maximum impact but no real loss of life. He must speak directly to the subconscious of the public. He must come and go

undetected, as subtle as the wind.

It would do the poet/revolutionary no good to be told what he should know, let

alone what he should do. If only things were so simple. Instead, his teachers can very helpfully inform him of the rules, and he must then proceed to laugh at their advice.

Creative disorientation is more than a grim necessity; it is our source of wealth, our means of transport. We must not mute our anxiety. Our creations must come

wriggling from the depths. To allow for this circuitous process to unfold, to pry open our previous if not our primal mode of vision, our teachers "take from our eyes the

day of our return."

3

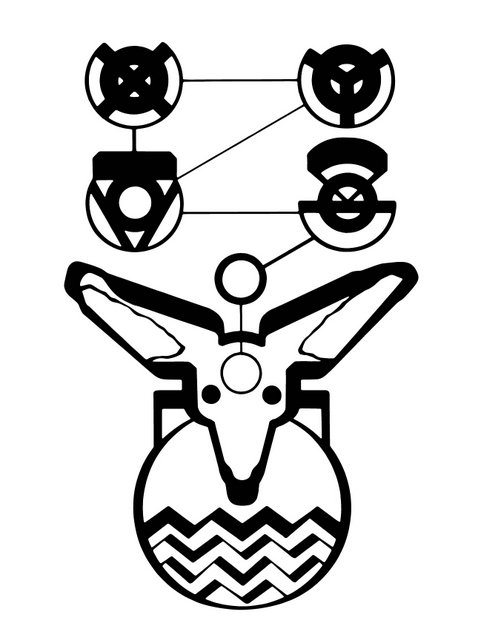

Brian George, Anubis Over the Ocean, 1991

If the poet is to be blind, it is also necessary that his art should be impeccable, for, at

the ocean's depth, say some, there are exobiological creatures that are more bizarre than fish. They too may be fishing, and it may not at first be clear which species is

the predator, which species is the food. The good poet should be able to sense if he is still among the living. Is he happy, having eaten, or is he no more than a hologram?

His life may not be other than a habit of projection, whose source has long since ceased to exist. The goal of the average traveler may be simply to avoid annihilation.

The good poet—the practitioner of metis, the man of many turnings—must do more.

He should not be a passive recipient of the strange. He must plunge into the mystery of what it means to have a body. He must then test to what extent he might be able to

hold his breath.

In Ancient Greece, it was thought that we saw the world by projecting light-beams

from our eyes, like superheroes. Contemporary scientists regard the concept as absurd. The eye is clearly a concave screen, onto which the world projects its

inverted image. But what if scientists are wrong, or, at the least, not entirely correct? If nature's laws are habits, which can change, then perhaps this mode of vision—the

"emission theory" as put forth by Plato, Ptolemy, and Euclid—was actually the common one in a previous world cycle.

In those days, we saw the world inside out, as from the backside of a mirror. Both

the eye and the light that it perceived were different. So too, our bodies were like nuclear reactors, which pulsed with a kind of telepathic force. When we asked that

the world reveal itself, there were few objects that would dare to disagree. We would not take "no" for an answer. To see was an active art. Or, one could also say: to see

was to act, and such action was an archaic science, as much as it was an art. From under layers of nerves and muscles, we could see a skeleton flash. We could see the

sap circulate through the veins of a growing leaf. As from an anteroom to the Earth, we could see our life's beginning, and its end. Upon entering an atom, we could track

each electron's orbit. We could enter the locked spirals of our DNA, there to read the histories that have been classified as "junk," there to determine how, from our

prototype, every species has devolved.

"Were these general powers?" we might reasonably ask. There were no doubt those,

the poet/seers, for whom vision was a branch of yoga or gymnastics, who had cultivated skills of which others could only dream. This does not mean, however,

that the eyes of the early race were not different from ours. If their numbers were fewer, there may have been far greater quantities of vision to be shared. The group's

powers of emission were not dispersed among 8 ½ billion strangers.

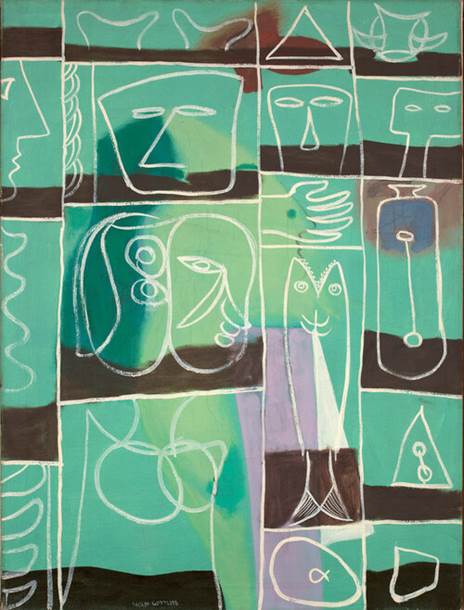

Adolph Gottlieb, Mariner's Incantation, 1945

Now, the poet must find his own way back beyond the Deluge, sailing into and up its

mind-destroying fear, and then out beyond the violence of the mile-high wave. There, in a contest with his own stupidity, and, if all goes according to schedule, with

some small amount of help, he must once more learn to see. A great sucking sound will make his ears pop. His "I" will once more turn into a "we," into the roar of a

cacophonous collective.

The wave, when it withdraws, will have swept off all of the bad art that was heaped

up during the time-cycle, leaving only some few precious relics in the sand. If "seeing is believing," as is often said, at the mirror's back we will not have long to

wait. Not darkly, but face to face, we will there see the designers of our nonsensical curriculum. They will not prove to be strangers, after all. We will there learn who

among them has played games with our memory, who among them may have put words in our mouths. We will there see who has nudged us, trial by trail, little death

by big death, dream by waking dream, towards an end that preexisted our first baby steps towards vision.

We will there be as eight-armed ships. We will there be as luminous eyeballs. We will there be imploded suns. We will there be the fish-suited messengers that Sirius

once sent to Assyria. Our dangerousness will remove the majority of our doubts about self-defense. If we do not mind being laughed at, we can then dare to begin to

communicate what we know.

Notes

1) Tao Te Ching, translations by Charles Muller and Yi-Ping Ong and also John H. McDonald

2) Diana Reed Slattery, "Shifting to a Psychedelic World Culture," posted on

"Reality Sandwich," May 23rd, 2008

|